I really enjoyed the Jonathan Rauch column I reviewed because it gave an answer to my favorite question: what caused the decades-long decline of social capital? All forms of civic engagement—working for a political party, going to church, volunteering for Kiwanis, even bowling—require trust in an institution, in some type of structure that asks for buy-in from its participants.

Even bowling in a league requires people to become a "member" of the league and follow its rules.

The Atlantic ran a story about how the end of the landline is affecting modern families. The more telling tale is the rise of viewing devices; each house having multiple flat screens, smartphones, tablets, and laptops for each family member to watch their own show.

TV monoculture is over because producers no longer have to create shows that appeal to everyone. Family viewing—itself an institution, featuring two dictators (the parents) determining what is best for the proletariat (the kids)—is a thing of the past. Each member has their own device and can watch their own type of show.

The atomization of the family unit is moving people toward more private and individual lives, and away from the structures that invite people into public life, or even the family room.

Helicopter Parenting

The authors of The Coddling of the American Mind, the author of iGen, and websites like Let Grow blame a lot of the problems with today's youth--like anxiety and depression--on helicopter parenting. They say it is important for kids to have unstructured unsupervised play and parents are not allowing that.

But what if it's not that simple? What if kids are leaving the house less because they don't want to, because they like the quality of entertainment at their disposal and don't feel compelled to leave the house to make new friends of have social interactions with current ones?

The average family is also smaller, so there is less experience with compromise. They don't have the necessary experience for negotiating public life and working through conflict.

Social Diabetes

Here's what I don't get: why does it feel good to do something that is bad for us?

Why does it feel better to read a book on philosophy in a quiet room than to attend weekly Mass?

Why do I enjoy sitting on my living room couch, scrolling through my Twitter timeline, putting a show for my son on our TV, and putting Netflix on our laptop for my daughter, as opposed to picking something we all can watch?

Why do I write blog posts about how disappointing I find our politicians to be instead of volunteering for the campaign of someone I believe can do better?

Eating I understand. Sugar is rare in the natural world, and our bodies need it in small amounts, so we have adapted traits that tell us to load up when something tastes sweet, knowing we might not find it again for weeks.

We understand that high levels of sugar are bad for us and are at least working on it. I feel like we understand the harmful effects of pulling away from public life, but we're not too concerned about it. There are public campaigns about opioid abuse and suicide, but not about their root causes: loneliness and isolation.

People choose personalization over sharing and compromise when given the choice. We choose to unite over a common enemy rather than work on a common project. The upshot is that this is terrible for society. It brings out the worst in our tribal impulses. We have no experience sharing in our personal life and expect democracy and society to be the same.

We're all coming up with Type II social diabetes but we're okay with the tradeoff because the saccharine personalization of entertainment tastes so damn good.

It could be that we've just never had the opportunity for personalization in human history, so we don't know how to deal with its externalities. But I'm growing less confident that we'll get to a point where we realize how bad this is for all of us and actually do something about it.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Best of 2019

Below are the best things I read or listened to in 2019.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

Jonathan Rauch

"In many respects, institutions are enemies of tribalism, at least in the context of a liberal society. By definition, they bring people together for joint effort on common projects, which builds community. They also socialize individuals and transmit knowledge and norms across generations. Because they are durable (or try to be), they tend to take a longer view and discourage behavior that considers only self-interest in the very short term...

"The more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."

Jonathan Rauch and Ray La Raja

"Turnout in primaries is notoriously paltry, and those who do show up are more partisan, more ideological, and more polarized than general-election voters or the general population. They are also wealthier, better educated, and older.”

"When party insiders evaluate candidates, they think about appealing to overworked laborers, harried parents, struggling students, less politicized moderates, and others who do not show up on primary day—but whose support the party will need to win the general election and then to govern. Reducing the influence of party professionals has, as Shafer and Wagner observe, amplified the voices of ideological activists at the expense of rank-and-file voters."

Ross Douthat

"[W]e should subdivide the “despair” problem into distinct categories: A drug crisis driven by the spread of heroin and fentanyl which requires a drug policy solution; a surge in suicides and depression and heavy drinking among middle-aged working-class whites to which economic policy might offer answers; and an increase in depression and suicide generally, and among young people especially, that has more mysterious causes (social media? secularization?) and might only yield to a psychological and spiritual response...

"But at the same time the simultaneity of the different self-destroying trends is a brute fact of American life. And that simultaneity does not feel like just a coincidence, just correlation without entanglement — especially when you include other indicators, collapsing birthrates and declining marriage rates and decaying social trust, that all suggest a society suffering a meaning deficit, a loss of purpose and optimism and direction, a gently dehumanizing drift."

Peter Beinart

“There is a secrecy “heuristic”—a mental shortcut that helps people make judgments. “People weigh secret information more heavily than public information when making decisions,” they wrote. A 2004 dissertation on jury behavior found a similar tendency. When judges told jurors to disregard certain information—once it was deemed secret—the jurors gave it more weight.

"While it’s unlikely Trump has heard of the secrecy heuristic, his comments about murder on Fifth Avenue suggest he grasps it instinctively. He recognizes that people accord less weight to information that nobody bothers to conceal. If shooting someone were that big a deal, the reasoning goes, Trump wouldn’t do it in full public view.

"By openly asking Ukraine and China to investigate a political rival, Trump expressed confidence that he’s doing nothing wrong. And while one might think the majority of Americans would view Trump’s confidence as an outrageous sham, academic evidence suggests that con men can be surprisingly difficult to unmask."This article is what made me think that Trump truly has something to hide in his tax returns. It's the only thing he keeps secret, which is probably why I give it more weight. But given what we know about Trump, it's probably less nefarious and more embarrassing. My guess is that he doesn't have as much money as he wants people to think.

"The Ideological Turing Test: How to Be Less Wrong"

Charles Chu

Charles Chu

"What we believe as ‘true’ today is just a small blade of grass in a miles-wide graveyard of ideas.

"Much of what we believe today is doomed to join other infamous dead theories like Lamarckism (“Giraffes have long necks because they used them a lot.”), bloodletting (“Let me put a leech on your forehead. It’ll cure your allergies. I promise.”), and phrenology (“I’m better than you because I have a bigger head.”)...

"Bryan Caplan says that I should understand my opponents’ ideas so well that they can’t tell the difference between what I am saying and what they believe."

A guide to the most—and least—politically open-minded counties in America"

Amanda Ripley, Rekha Tenjarla, Angla Y. He

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

John Wood Jr.

"Klein worries that the solutions to the problems that concern Haidt and Lukianoff are also wicked in precisely the opposite direction. Civility and moderation, desirable qualities for political discourse and decision making, can numb us to the imperative of social change.

"Klein argues that successful activism has a history of making people uncomfortable, who would otherwise simply ignore injustice. 'Confrontation is unpopular, and often necessary, in part to get people to see things they don’t want to see.'

"We must realize that the maintenance of dignity in activism does not require the abandonment of fervor."This too sparked a blog post of mine.

Podcasts

The Rewatchables: The Shining featuring Bill Simmons, Sean Fennessey, and Chris Ryan

The Ezra Klein Show: Michael Lewis reads my mind

The Ezra Klein Show: Matt Yglesias and Jenny Schuetz solve the housing crisis

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"As it took its first baby steps, the Blue Tribe started asking itself “Who am I? What defines me?”, trying to figure out how it conceived of itself. New Atheism had an answer – “You are the people who aren’t blinded by fundamentalism” – and for a while the tribe toyed with accepting it. During the Bush administration, with all its struggles over Radical Islam and Intelligent Design and Faith-Based Charity, this seemed like it might be a reasonable answer. The atheist movement and the network of journalists/academics/pundits/operatives who made up the tribe’s core started drifting closer together.

Gradually the Blue Tribe got a little bit more self-awareness and realized this was not a great idea. Their coalition contained too many Catholic Latinos, too many Muslim Arabs, too many Baptist African-Americans. Remember that in 2008, “what if all the Hispanic people end up going Republican?” was considered a major and plausible concern. It became somewhat less amenable to New Atheism’s answer to its identity question – but absent a better one, the New Atheists continued to wield some social power.

Between 2008 and 2016, two things happened. First, Barack Obama replaced George W. Bush as president. Second, Ferguson. The Blue Tribe kept posing its same identity question: “Who am I? What defines me?”, and now Black Lives Matter gave them an answer they liked better “You are the people who aren’t blinded by sexism and racism.”"BOOK REVIEW: THE SECRET OF OUR SUCCESS"

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

"Henrich discusses pregnancy taboos in Fiji; pregnant women are banned from eating sharks. Sure enough, these sharks contain chemicals that can cause birth defects. The women didn’t really know why they weren’t eating the sharks, but when anthropologists demanded a reason, they eventually decided it was because their babies would be born with shark skin rather than human skin."One of the reasons I like Scott is the he is critical of his own beliefs. This book is actually an argument against rationalism. The irrational idea that eating shark will give your baby shark skin is an idea that survived for so long that it must have a reason, however irrational it appears.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

"If you were to put a gun to my head and force me to break down the importance of various factors in contributing to wage decoupling, it would look something like (warning: very low confidence!) this:Shameless Self-love

– Inflation miscalculations: 35%

– Wages vs. total compensation: 10%

– Increasing labor vs. capital inequality: 15%

—- (Because of automation: 7.5%)

—- (Because of policy: 7.5%)

– Increasing wage inequality: 40%

—- (Because of deunionization: 10%)

—- (Because of policies permitting high executive salaries: 20%)

—- (Because of globalization and automation: 10%)"

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

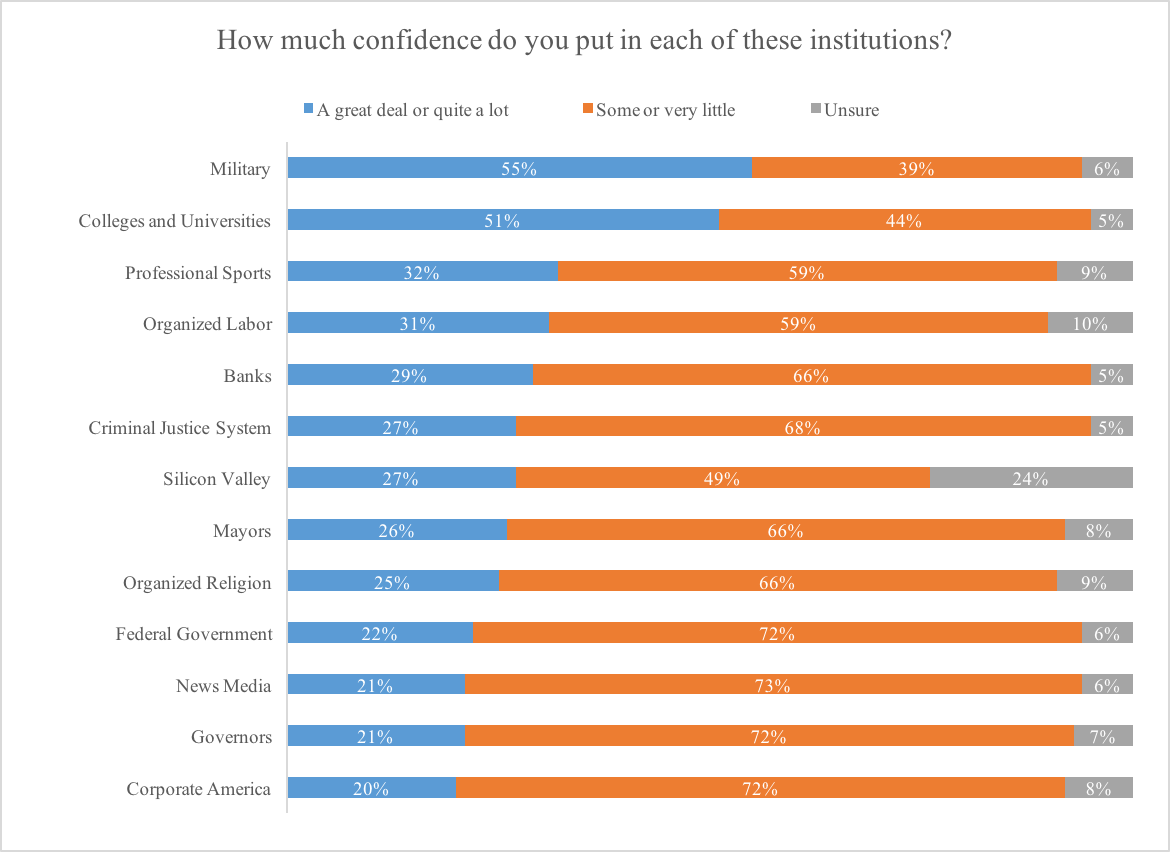

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

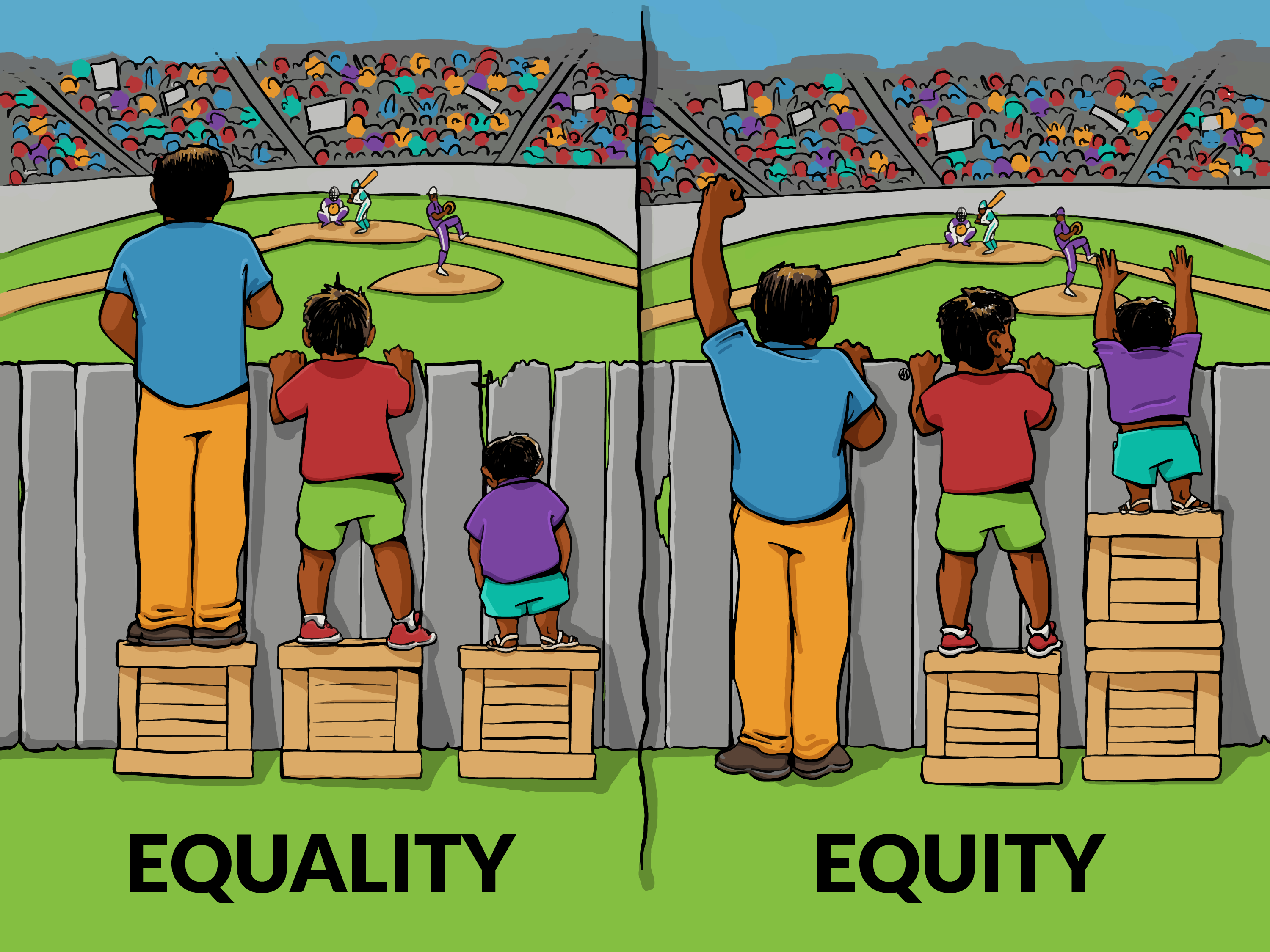

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

A National Network of Community

One pattern Tyler Cowen observes in The Complacent Class is the growing reluctance of Americans to switch jobs and move to another state.

A common response is that poor people don't have the financial means to move, even if it means a better job. I'm not sure I entirely buy that. At the very least, it's only telling part of the story.

So what is keeping low-wage workers in low-productivity towns?

Personally, the number one reason I don't move is that my family is here and I don't like meeting new people. I have a very narrow window for people I'm not related to that I actually like spending time with. But if I knew MY TYPE OF PEOPLE would be in a new community where I have a job opportunity, I might consider moving.

That is why I wonder how much the decline of attendance in national institutions have had on geographic mobility. There has been a rise in independent protestant and Evangelical churches over the past 30 years and a commensurate decline in Catholic, Episcopal, Southern Baptist and United Methodist churches.

The advantage of having a national brand of religion is that you can be sure a community of like-minded believers will be waiting for you when you move to a new area. The same goes for Rotary International or any other civic organization.

When institutions are localized, it stymies the incentive to move somewhere different where you might not feel welcomed. Having a social infrastructure in place, where you already have some type of membership, at least gets you a foot in the door.

If family is what keeps me rooted, community is what can lure me away. A national network of ideologically-driven colleges and universities might be able to Make America Mobile Again.

This article traces it a little better and finds a similar conclusion.

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Strong institutions or inclusive parties?

I.

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

"Paradoxically, partisanship has never been stronger, but the party organizations have never been weaker — and this is not a paradox at all. When they had the capacity to do so, party organizations engaged citizens in volunteer work, local party clubs, and social events, giving ordinary people a sense of political engagement that merely voting or writing a check cannot provide. Until they lost the power to do so, they road-tested and vetted political candidates, screening out incompetents, sociopaths, and those with no interest in governing. When they could, they used incentives like jobs, money, and protection from primary challenges to get legislators to work together and accept tough compromises. Perversely, the weakening of parties as organizations has led individuals to coalesce instead around parties as brands, turning organizational politics into identity politics.

To put the point another way, the more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."And later:

"Getting traction against affective polarization and tribalism will require some direct measures, such as civic bridge-building. Even more, it will require indirect measures, such as strengthening institutions like unions, civic clubs, political-party organizations, civics education, and others. Above all, it will require re-norming: rediscovering and recommitting to virtues like lawfulness and truthfulness and forbearance and compromise."I want to believe that strong parties can build social capital and strengthen communities. Can we have that without pushing outside candidates to the margins?

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

- Strong institutions might allay our country's current tribal crisis, but I'd really like to research this idea more.

- If the result of weakening political parties is that they make room for outside candidates who otherwise would have run as a third party, I think that is a good thing.

- I'm not convinced that we can revive the Democrat and Republican parties to their 1950s strength. We (meaning Millenials and Gen Z) might have to put our faith in new institutions.

- If colleges follow the Jon Haidt model and be transparent about their ideology, people will choose whichever matches their preference. Investment in more colleges, especially in this model, might lead to strong institutions that people trust, which will build loyalty to the institution that can then reduce tribalism.

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

What if they don't want your help?

I've always admired the progressives' work to advocate on behalf of the poor, downtrodden, marginalized groups of society. But lately I've begun to wonder if their efforts are in vain.

Are they too performative? Are they overapplying instances of oppression? Are they trying to fix a problem that isn't actually a problem?

Marriage

This Quillette story deals with how elites use coded language and espouse particular beliefs as ways of signaling their class status. Ultimately, I think the author engaged in bad-faith reasoning in an otherwise well-written and researched column. I happen to think progressives, for the most part, are doing what they think is in the best interest of the oppressed.

However, the author makes an interesting point, noting that:

"...in 1960 the percentage of American children living with both biological parents was identical for affluent and working-class families—95 percent. By 2005, 85 percent of affluent families were still intact, but for working-class families the figure had plummeted to 30 percent.

Upper-class people, particularly in the 1960s, championed sexual freedom. Loose sexual norms spread throughout the rest of society. The upper class, though, still have intact families. They experiment in college and then settle down later. The families of the lower class fell apart. Today, the affluent are among the most likely to display the luxury belief that sexual freedom is great, though they are the most likely to get married and least likely to get divorced."I don't know that I completely buy the notion that hippies are the cause of the dissolution of the working class family unit (but Mary Eberstadt thinks so), but those marriage rates by class are important figures.

I'd like to probe deeper into what kept poor families together prior to the 1960s? Was social norms and fewer working opportunities for women keeping them in bad marriages? Divorce tends to correlate with money problems; perhaps stronger unions and less inequality kept poor families together?

Microaggressions

I'm all for bringing as many people into the American fold as possible. If there is a way for minorities to feel more welcome at college, I'd like to hear more. But I suspect that many progressives are trying solve a problem on behalf of a group, when it's only a "problem" for a very small portion of said group.

There's the poll noting that only 2 percent of Latin Americans actually prefer the term "Latinx."

Writing in The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf notes that many colleges are using examples of phrases to avoid as they are "racial microaggressions." However, he cites a Cato/YouGov survey on free speech and tolerance that finds:

"Telling a recent immigrant, “you speak good English” was deemed “not offensive” by 77 percent of Latinos; saying “I don’t notice people’s race” was deemed “not offensive” by 71 percent of African Americans and 80 percent of Latinos; saying “America is a melting pot” was deemed not offensive by 77 percent of African Americans and 70 percent of Latinos; saying “America is the land of opportunity” was deemed “not offensive” by 93 percent of African Americans and 89 percent of Latinos; and saying “everyone can succeed in this society if they work hard enough” was deemed “not offensive” by 89 percent of Latinos and 77 percent of African Americans."PC Language

Finally, in The Atlantic, Yascha Mounk writes about political correctness as mentioned in the Hidden Tribes Report.

"Among the general population, a full 80 percent believe that “political correctness is a problem in our country.” Even young people are uncomfortable with it, including 74 percent ages 24 to 29, and 79 percent under age 24. On this particular issue, the woke are in a clear minority across all ages."Mounk then goes on to describe the demographics of those espousing PC language.

"So what does this group look like? Compared with the rest of the (nationally representative) polling sample, progressive activists are much more likely to be rich, highly educated—and white. They are nearly twice as likely as the average to make more than $100,000 a year. They are nearly three times as likely to have a postgraduate degree. And while 12 percent of the overall sample in the study is African American, only 3 percent of progressive activists are. With the exception of the small tribe of devoted conservatives, progressive activists are the most racially homogeneous group in the country."Rich, educated, and white? That sounds a lot like the elitist group described in the Quillette column. Now, just because a group is racially homogeneous and ideologically orthodox does not mean they have a hidden elitist agenda. But it does weaken their "if you disagree with me you're a racist bigot" argument when most minorities are outside their bubble and, in fact, disagreeing with them. And it does suggest they do not necessarily represent the values of the people they are trying to help.

Friday, November 8, 2019

Why I'm not an activist

“there is no such thing as a not-racist idea,” only “racist ideas and antiracist ideas.”

-Ibram X. Kendi

"Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."This is a defense of moderation, or better yet, my concept of civility. Actvists tend to commit the third great untruth: believing that life is a battle between good people and evil people. And since those not fighting against us are not fighting with us, they have chosen evil.

-President George W. Bush

Moderates are hard to define because we are not a monolith. But here are some reasons we do not engage with your wars.

The wrong action is often worse than no action. In the President Bush quote above, invading Iraq ended up being a terrible idea. Many moderates are slow to action, requiring careful consideration, because taking the wrong action is worse than no action. We would have been better off never invading Iraq, obviously. Inaction probably delayed the civil rights movement, but I believe that is the exception rather than the rule.

I don't trust all of the people on your side. Fighting racism sounds great. I would love to punch a Nazi in the face. But I have some reservations. First, the Kendi quote above comes from a review of his book in which he proposes an anti racist amendment to the Constitution that would:

"establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees... The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas."That sound pretty far from punching Nazis and terrifyingly totalitarian. Oh, and about punching Nazis. I don't trust your side to determine who is a Nazi. Especially after Antifa beat a Bernie Sanders supporter just for carrying an American flag.

I don't prioritize my desires the same as you do. This isn't about privilege; it's about what I think is most important. I don't think we can have a functioning society without trust, which is why I prioritize depolarization above Medicare for All or building a wall.

I would love to have a health care system that provides for everyone and costs less. I'm skeptical it can be done, but I'm more worried about what happens when you try to force half the country off the private insurance plan they prefer. Our system does not work without cooperation and I'd rather repair the system than blow it up.

I don't think all your facts are accurate. I hate racist police officers. The one who shot Philando Castille should absolutely be in prison. I'll sign that petition for you. But I won't march with a group that also marches for Michael Brown, whom I believe was shot because he attacked a police officer.

I'm also picky about systemic racism. Data has convinced me there is no racial bias in arrests for violent crimes. Sentencing? Yeah, there probably is a racial bias. But in my experience, the activists don't offer an à la carte menu to support. It's very all or nothing. Don't confuse my nuanced thinking with inaction.

I hate coercion. I don't love the status quo, but I would rather live in a world with current levels of inequality and injustice than one in which we give one person or party absolute power to change things as they see fit. There's just no way that power won't be abused once it falls into the wrong hands. Which it will. The incentives are too great.

Friday, October 25, 2019

Race, Grammar, Bullying, and Belonging

Some years ago I began the David Foster Wallace essay "Authority and American Usage." As a writer, I'm interested in grammar, particularly the battle between prescriptive and descriptive advocates, and Wallace seemed a good authority on the issue.

I read the essay before bed and never finished it. I picked it up again a few weeks ago and finally finished. I'm glad I did because it took many turns I did not see coming.

Wallace begins with a mention of how he was a grammar Nazi (he prefers SNOOT, or Syntax Nudniks of Our Time ) as a child and how it held him back with his peers.

This is a lesson many white children do not have to learn. Their dialects seem to more closely transition into SWE and there isn't an aversion to distancing themselves from an outgroup, since SWE is mostly spoken by white people.

I read the essay before bed and never finished it. I picked it up again a few weeks ago and finally finished. I'm glad I did because it took many turns I did not see coming.

Wallace begins with a mention of how he was a grammar Nazi (he prefers SNOOT, or Syntax Nudniks of Our Time ) as a child and how it held him back with his peers.

"... this reviewer regrets the bio-sketch's failure to mention the rather significant social costs of being an adolescent whose overriding passion is English usage..."He then moves into how there are are myriad dialects other than Standard Written English, and we all (Black, White, Asian, Latinx, etc.) speak more than one of them.

"Fact: there are all sorts of cultural/geographical dialects of American Usage — Black English, Latino English, Rural Southern, Urban Southern, Standard-Upper Midwest, Maine Yankee, East-Texas Bayou, Boston Blue-collar, on and on... many of these non SWE (standard written english) type dialects have their own highly developed and internally consistent grammars, and that some of these dialects' usage norms actually make more linguistic/aesthetic sense than do their Standard counterparts... nearly incomprehensible to anyone who isn't inside their very tight and specific Discourse Community (which of course is part of their function)."Wallace then goes into the tribal nature of learning a local dialect: it has an ingroup/outgroup function.

"When I'm talking to RMers (Rural Midwestern) I tend to use constructions like "Where's it at?" for "Where is it?"and sometimes "He don't" for "He doesn't." Part of this is a naked desire to fit in and not get rejected ... but another part is that ... these RMisms are in certain ways superior to their standard equivalents."

"Whether we're conscious of it or not, most of us are fluent in more than one major English dialect and in several subdialects and are at least passable in countless others.... the dialect you use depends mostly on what sort of Group your listener is part of and on whether you wish to present yourself as a fellow member of that Group."

"A dialect of English is learned and used either because it's your native vernacular or because it's the dialect of a Group by which you wish (with some degree of plausibility) to be accepted. And although it is a major and vitally important one, SWE is only one dialect... There are situations ... in which faultlessly correct SWE is not the appropriate dialect."Now it gets really interesting. Wallace does something that Chris Rock talks about in his latest Netflix special that kinda sounds like justifying bullying. But it also supports the importance of free play and socialization for children. They need to learn from one another as much as they learn from adults.

"Childhood is full of such situations. This is one reason SNOOTlets tend to have such a hard time of it in school... The elementary-school SNOOTlet ... is duly despised by his peers and praised by his teachers. These teachers usually don't see the incredible amounts of punishment the SNOOTlet is receiving from his classmates, or if they do see it they blame the classmates and shake their heads at the sadly and viscous and arbitrarily cruelty of which children are capable.

"Little kids in school are learning about Group-inclusion and -exclusion and about the respective rewards and penalties of same and about the use of dialect and syntax and slang as signals of affinity and inclusion. Kids learn this stuff not in Language Arts or Social Studies but on the playground and on the bus and at lunch... what the SNOOTlet is being punished for is precisely his failure to learn... the SNOOTlet is actually deficient in Language Arts. He has only one dialect. He cannot alter his vocabulary, usage, or grammar ... and these abilities are really required for "peer rapport" which is just a fancy academic term for being accepted by the second-most-important Group in a little kid's life."

"One is punished in class, the other on the playground, but both are deficient in the same linguistic skill—the ability to move between various dialects and levels of "correctness," the ability to communicate one way with peers and another way with teachers and another with family and another with T-ball coaches and so on. "Finally, Wallace comments on race. This sounds like roundabout way of talking about "talking white," a contentious subject that many people think is made up. Others, like John McWhorter, think are all too real. It's also a good explanation of why learning Standard Black English, and dismissing SWE, is so important to many African Americans, it helps ensure ingroup distinction.

This is a lesson many white children do not have to learn. Their dialects seem to more closely transition into SWE and there isn't an aversion to distancing themselves from an outgroup, since SWE is mostly spoken by white people.

"Here is a condensed version of a spiel with certain black students who were bright and inquisitive as hell and deficient in what US higher education considers written English facility:Overall it was a really interesting read about how people use language to both fit in and to exclude.

'...when you're in a college English class you're basically studying a foreign dialect... the SBE (Standard Black English) you're fluent in is different from SWE in all kinds of important ways...

It's not that you're a bad writer, it's that you haven't learned the special rules of the dialect they want you to write in."

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

Nora Durst is full of sh*t

I've read some people assume that Nora's story about traveling to the "other side" was God's honest truth. I disagree.

This is not a show about science fiction. The Leftovers is a show about how people respond to tragedy, so it's important to understand what I mean by tragedy.

Tragedy is something that does not make rational sense. It is absurd. It is what talking heads on TV talk about when they describe something as a "senseless act of violence" because it makes no sense to us.

The best example is the Sandy Hook shooting. A young man took his gun and killed 20-something children whom he did not know. That sentence makes no goddamn sense. He gained no utility from that act.

Not only was this act terrifying because we can empathize with those parents, it was terrifying because it brought down the illusion of order in our world. It showed us that things that make no sense can happen to anyone.

The way people respond to this type of tragedy is by creating a story. Some choose the story of easy access to guns. For some it's a lack of mental health support. For others it's violent video games or drugs or social isolation. But none of these stories really make the tragedy make sense, but they are a better story then senselessness.

The way people respond to this type of tragedy is by creating a story. Some choose the story of easy access to guns. For some it's a lack of mental health support. For others it's violent video games or drugs or social isolation. But none of these stories really make the tragedy make sense, but they are a better story then senselessness.

My favorite example was a Facebook post from my old boss. A strong-faith Christian man, he wrote about how God was with those children when they died. It didn't make sense, but I could tell he put a lot of thought into it and it helped him process the tragedy and retain his faith.

In The Leftovers, it makes sense that church attendance would see a decline. The departure was so senseless, that people stopped being able to believe in something that helped their lives make sense. The Matt Jamison character works so hard to find dirt on the departed because he has to believe that they were taken for a reason.

But for most people it wasn't enough, so they began to create their own stories: the Guilty Remnant, Holy Wayne, the Eddie Winslow character, and Miracle, Texas. Even holdouts like Kevin Garvey eventually began to believe he was the second coming of Christ. Nora was the only character who refused to write her own fiction. She even made it her mission to expose frauds.

It also makes sense that the protagonist was a cop, someone who's role was to maintain order in the face is increasing disorder as people clung to crazier ideas to try and make sense of what happened.

It also makes sense that the protagonist was a cop, someone who's role was to maintain order in the face is increasing disorder as people clung to crazier ideas to try and make sense of what happened.

The finale wasn't a story about Nora finding out what happened to her family. It was a story about her finally creating her own story. If you pay attention, her tale concludes that her family is actually better off wherever they are. Self-delusion is the path to comfort and happiness in the face of tragedy. The awareness of senselessness will drown you. She had to find the perfect story to be able to move on and start her new life with Kevin.

Tuesday, October 15, 2019

The Limits of Empathy

I.

In the quantitative section of the GRE, there is a set of questions called Quantitative Comparison. It features four multiple choice answers that are always the same:

A: quantity A is greater

B: quantity B is greater

C: they are the same

D: it cannot be determined.

The best strategy is to try to prove D. The question involves a variable so you want to plug in different numbers (1, -1, 0) to show that sometimes A is greater and sometimes B is greater, so that you can prove D, which allows you to rule out A, B, and C.

This is the same strategy people use to disprove ideas they don't like. Is free speech a good idea? No, because Nazis shouldn't be able to say hateful things about minorities. Is abortion a good idea? No, because what if someone had aborted Ghandi, Einstein, or Oprah. The idea is that if you can find one example that isn't to your liking, you can rule out the whole spectrum of a topic and disprove its merit.

II.

I'm thinking about Ellen DeGeneres and how she defended sitting next to George W. Bush, saying she can be friends with someone she disagrees with. I know I'm Mr. Bipartisan. Mr. Depolarize America. Mr. Find Common Ground With Our Enemies. But I kind of think her critics have a point.

I'm going to stay away from the Iraq War (both because Obama was responsible for many civilian casualties when he was in office and because I don't know what Ellen's stance is) and focus on gay rights. W used his power in office to try to stop Ellen from marrying the person she loved. His actions directly harmed Ellen. For each individual, at a certain point a disagreement becomes an affront you are forced to take action on.

Chloe Valdary talks a lot about the importance of showing our enemies that we believe in their ability to change themselves, and how this is a more effective way of dealing with our outgroup than public shaming. If Ellen's conclusion is that she wants to keep W close in order to change his mind on issues or better understand his point of view, I would have found it to be a more convincing argument. But waving off his anti-gay rights stance as a "disagreement" makes it sound as if the issue is not important to her. And maybe it's not; that's up to her.

III.

I believe in empathy but I understand that it has limits. I also understand that the limits are different for each individual.

Conor Friedersdorf wrote about how it is more important to focus on our personal limits of a given topic, as opposed to being pro or against something. Likewise, I think it is important for everyone to be open about the limits of what they believe in.

I believe in free speech but I don't think powerful institutions, like the media or the president, should be able to lie to the public. I believe religious institutions should be able to ban homosexuality on their turf but the public realm should remain neutral. I believe guns should be legal but more heavily regulated so they are safer.

I also believe that a single example does not disprove the merit of a given stance, it only sets the limitation. Unlike the quantitative section of the GRE, ethics and social norms are fuzzy and debatable. That's why I think people are best served setting their own limitation before the person they are arguing with sets it for them.

I'd be curious to know what view on gay rights would be so extreme that it would cause Ellen to disassociate herself with Bush. Because that's the problem with the "be friends with people who disagree with me" mantra: it doesn't acknowledge extremism. Some people are not open to reason and not worth the time. And even the most tolerant human can think of a stance so horrid that they cannot be friends with a person who holds that stance.

So if I were Ellen's PR person, I'd have her clarify her limitations to the "I can be friends with people I disagree with" statement. Then I'd have her state that, in spite of Bush's war policies and gay rights views, here are the positive qualities about him that make him a valuable person. "I don't like his views on marriage equality but I've found that we can work together to do a lot to improve immigration reform." Or something like that.

Otherwise, it looks like her stance is "I disagree with war and anti marriage equality, but not as much as I like watching football with a former president."

In the quantitative section of the GRE, there is a set of questions called Quantitative Comparison. It features four multiple choice answers that are always the same:

A: quantity A is greater

B: quantity B is greater

C: they are the same

D: it cannot be determined.

The best strategy is to try to prove D. The question involves a variable so you want to plug in different numbers (1, -1, 0) to show that sometimes A is greater and sometimes B is greater, so that you can prove D, which allows you to rule out A, B, and C.

This is the same strategy people use to disprove ideas they don't like. Is free speech a good idea? No, because Nazis shouldn't be able to say hateful things about minorities. Is abortion a good idea? No, because what if someone had aborted Ghandi, Einstein, or Oprah. The idea is that if you can find one example that isn't to your liking, you can rule out the whole spectrum of a topic and disprove its merit.

II.

I'm thinking about Ellen DeGeneres and how she defended sitting next to George W. Bush, saying she can be friends with someone she disagrees with. I know I'm Mr. Bipartisan. Mr. Depolarize America. Mr. Find Common Ground With Our Enemies. But I kind of think her critics have a point.

I'm going to stay away from the Iraq War (both because Obama was responsible for many civilian casualties when he was in office and because I don't know what Ellen's stance is) and focus on gay rights. W used his power in office to try to stop Ellen from marrying the person she loved. His actions directly harmed Ellen. For each individual, at a certain point a disagreement becomes an affront you are forced to take action on.

Chloe Valdary talks a lot about the importance of showing our enemies that we believe in their ability to change themselves, and how this is a more effective way of dealing with our outgroup than public shaming. If Ellen's conclusion is that she wants to keep W close in order to change his mind on issues or better understand his point of view, I would have found it to be a more convincing argument. But waving off his anti-gay rights stance as a "disagreement" makes it sound as if the issue is not important to her. And maybe it's not; that's up to her.

III.

I believe in empathy but I understand that it has limits. I also understand that the limits are different for each individual.

Conor Friedersdorf wrote about how it is more important to focus on our personal limits of a given topic, as opposed to being pro or against something. Likewise, I think it is important for everyone to be open about the limits of what they believe in.

I believe in free speech but I don't think powerful institutions, like the media or the president, should be able to lie to the public. I believe religious institutions should be able to ban homosexuality on their turf but the public realm should remain neutral. I believe guns should be legal but more heavily regulated so they are safer.

I also believe that a single example does not disprove the merit of a given stance, it only sets the limitation. Unlike the quantitative section of the GRE, ethics and social norms are fuzzy and debatable. That's why I think people are best served setting their own limitation before the person they are arguing with sets it for them.

I'd be curious to know what view on gay rights would be so extreme that it would cause Ellen to disassociate herself with Bush. Because that's the problem with the "be friends with people who disagree with me" mantra: it doesn't acknowledge extremism. Some people are not open to reason and not worth the time. And even the most tolerant human can think of a stance so horrid that they cannot be friends with a person who holds that stance.

So if I were Ellen's PR person, I'd have her clarify her limitations to the "I can be friends with people I disagree with" statement. Then I'd have her state that, in spite of Bush's war policies and gay rights views, here are the positive qualities about him that make him a valuable person. "I don't like his views on marriage equality but I've found that we can work together to do a lot to improve immigration reform." Or something like that.

Otherwise, it looks like her stance is "I disagree with war and anti marriage equality, but not as much as I like watching football with a former president."

Thursday, October 3, 2019

The Great Activist Argument

There are several ways to deal with disagreement.

Segregation would seem more like federalism, which surprisingly has gained no traction in these highly contentious times. People have not warmed to the idea of carving out a reservation for their enemies to do whatever they want as long as they stay in their area.

Domination is popular. People want a tough guy in the white house who will Executive Order the crap out of their enemies.

The Great Activist Argument

Progressive activists have a powerful rhetorical tool: BuT wHaT aBoUt SlAvErY? Here's why it works so well:

The fact that progressive activists were right to use domination physically (Civil War) and politically/socially (Civil Rights Movement), even when unpopular, reinforces their belief that as long as they are on the side of the oppressed, they are always right and justified in using dominance, in spite of being unpopular.

I hate domination/coercion tactics. But I have trouble coming up with a good argument against this. It's difficult to create a theory that makes an exception for domination. I don't know how to tell when the next Obvious Wrong like slavery will appear. I can only say with confidence that 99 times out of 100 it will not be judged the way we judge slavery but will be more like siding with the transgender woman who demands immigrants wax her scrotum.

Climate Change

Climate Change is another good argument for domination. Segregation won't work. If the biggest polluters (China) don't cut back C02 emissions, it doesn't matter what everyone else does. And compromise doesn't seem like a great option; cutting back on greenhouse gases is the only option sans some type of geoengineering.

This is where persuasion is really necessary. The idea is that if the US can go green, the rest of the world will follow. But how can we convince our outgroup in America that reducing CO2 emissions is for their benefit as well?

First, you'd have to understand the outgroup. They are mostly conservative or very pro-business. So things like tax credits for solar energy is a good start. It's not coercive and puts money in their pocket. Promoting nuclear energy makes sense. It just replaces coal powered plants so the effect on the economy is zero sum but the effect on the environment is huge (of course I'm very worried about the tail risks of nuclear plants after watching HBO's Chernobyl.)

Next, you have to understand factionalism. The biggest thing stopping this brand of conservatives from getting on board is their proclivity for owning the libs. You need to make room for them to create their own platform. It has to feel like their own idea.

This is where groups like Better Angels can really help. They have a rule that they never meet without an equal number of reds and blues. Every major communication about climate change, whether a protest or a Green New Deal legislation, should be co-led by a liberal and conservative. Greta Thunberg and AOC are not going to convince conservatives that they are wrong. If the effort is led by AOC and, say, Lindsay Graham, it will be viewed as a partnership and become less tribal. It becomes about the platform and not about which tribe is right.

- Compromise. I give up something I want, you give up something we want, so that we can both get something we both want.

- Segregation. I do my thing, you do your thing, and we stay out of one another's way.

- Domination. I force you into doing what I want.

Segregation would seem more like federalism, which surprisingly has gained no traction in these highly contentious times. People have not warmed to the idea of carving out a reservation for their enemies to do whatever they want as long as they stay in their area.

Domination is popular. People want a tough guy in the white house who will Executive Order the crap out of their enemies.

The Great Activist Argument

Progressive activists have a powerful rhetorical tool: BuT wHaT aBoUt SlAvErY? Here's why it works so well:

- Domination worked

- Federalism/segregation would not have worked. There would still be slavery.

- Compromise would not have worked. Accepting anything less that "end slavery" would have been a weak compromise for the north.

The fact that progressive activists were right to use domination physically (Civil War) and politically/socially (Civil Rights Movement), even when unpopular, reinforces their belief that as long as they are on the side of the oppressed, they are always right and justified in using dominance, in spite of being unpopular.

I hate domination/coercion tactics. But I have trouble coming up with a good argument against this. It's difficult to create a theory that makes an exception for domination. I don't know how to tell when the next Obvious Wrong like slavery will appear. I can only say with confidence that 99 times out of 100 it will not be judged the way we judge slavery but will be more like siding with the transgender woman who demands immigrants wax her scrotum.

Climate Change

Climate Change is another good argument for domination. Segregation won't work. If the biggest polluters (China) don't cut back C02 emissions, it doesn't matter what everyone else does. And compromise doesn't seem like a great option; cutting back on greenhouse gases is the only option sans some type of geoengineering.

This is where persuasion is really necessary. The idea is that if the US can go green, the rest of the world will follow. But how can we convince our outgroup in America that reducing CO2 emissions is for their benefit as well?

First, you'd have to understand the outgroup. They are mostly conservative or very pro-business. So things like tax credits for solar energy is a good start. It's not coercive and puts money in their pocket. Promoting nuclear energy makes sense. It just replaces coal powered plants so the effect on the economy is zero sum but the effect on the environment is huge (of course I'm very worried about the tail risks of nuclear plants after watching HBO's Chernobyl.)

Next, you have to understand factionalism. The biggest thing stopping this brand of conservatives from getting on board is their proclivity for owning the libs. You need to make room for them to create their own platform. It has to feel like their own idea.

This is where groups like Better Angels can really help. They have a rule that they never meet without an equal number of reds and blues. Every major communication about climate change, whether a protest or a Green New Deal legislation, should be co-led by a liberal and conservative. Greta Thunberg and AOC are not going to convince conservatives that they are wrong. If the effort is led by AOC and, say, Lindsay Graham, it will be viewed as a partnership and become less tribal. It becomes about the platform and not about which tribe is right.

Thursday, September 5, 2019

Ideological Equity

I.

The Big Sort dealt with the lack of political diveristy in communities. But it didn't look at the lack of political diversity in institutions, the places we work.

I was thinking of the John Rawls "original position" thought experiment and how people might want to design the ideological diversity of our country's most powerful institutions. Should we tweak things so there is more diversity of thought, or keep it status quo, with certain institutions dominated by certain ideology?

Liberal ideology dominates the media and education. Opening up discussion to different thought risks losing domination of these industries, so I can understand the (Robin DiAngelo voice) fragility among journalists and professors to ideological diversity. However, I'm sure liberals would agree that the military and police force could benefit from ideological diversity since they are dominated by conservatives.

Conservatives might be okay with collateral damage, waterboarding, and "leaning forward" because the ends justify the means when it comes to war. Liberals in the military would push back against this, and I think that is a good thing, but would people be willing to make these trade offs to achieve ideological equilibrium?

I tried to think of institutions lacking ideological diversity and this is what I came up with:

Liberal leaning

My gut instinct is that the tech sector leans left. While it is a business, Google's reaction to the James Damore memo suggests that liberal ideology is the dominant view. But maybe they're an outlier.

II.

So back to the Rawls experiment. If you could design a world, would you want ideological equality in all major institutions or would you keep them the way they are, assuming that you would be born into this world with a predetermined, unfixed ideology that you do not choose. You might be a liberal police chief or a conservative humanities professor, surrounded by people who oppose your beliefs.

A good argument in favor of the status quo is that there already is an ideological equilibrium. Institutions can be dominated by ideology, as long as there is a balance among the institutions rather than within the institutions. So if you have conservatives in the military, police, and on Wall Street, they are balanced by liberals in universities, major news organizations, and in the classroom.

A good argument against that idea is that not all major institutions are the same. In fact, I'd say that the military and police and quite powerful, as they possess the threat of force. Wall Street is exceptionally strong as well, as we saw during the 2008 financial crisis.

While the media is powerful, it's becoming more diffuse and could never match the threat of a rogue police state. So while the number of major industries might be in balance, I think the power leans in the direction of conservatives.

Also, a lot of the recent research I read shows that echo chambers breed extremism. These institutions become feedback loops where the more orthodox they get, the more hostile they become to outside points of view, which leads the few dissenters leaving, which leads to more orthodoxy. So keeping things status quo means that these institutions are going to get more extreme and dangerous.

III.

So if I had to choose, I would want ideological equilibrium.( I don't have skin in the game, since my views of rationalism and constitutional localism are not at risk of losing any power. We don't have any. We are minorities in all institutions.) But I think putting a check on power is something we can all agree on.

As much as I preach for ideological diversity in higher education, after working on this post I have come to have my doubts. If I'm a liberal, I'm not sure I would give up my dominance without assurance that there was more ideological diversity in the military (technically, all you need is a liberal in the White House, as they command the military).

But we don't have to operate in Rawls' hypothetical world-building. We can build a system based on the critical-theory left's ideas of equity. It involves a level of coercion I am not comfortable with, and it seems like it would be unpopular, but if you framed it in terms of a tit-for-tat trade, you might have something.

In a previous post, I argued that voting for extreme candidates ensures gridlock and pushes power to the local level. But there is another type of gridlock. It isn't just extreme left vs. extreme right. There can also be extreme left vs. moderate left, and extreme right vs. moderate right.

I think that's what we used to have and it seems like more got done. If this holds true for the private sector, then ideological diversity within institutions is a more efficient system.

The Big Sort dealt with the lack of political diveristy in communities. But it didn't look at the lack of political diversity in institutions, the places we work.

I was thinking of the John Rawls "original position" thought experiment and how people might want to design the ideological diversity of our country's most powerful institutions. Should we tweak things so there is more diversity of thought, or keep it status quo, with certain institutions dominated by certain ideology?

Liberal ideology dominates the media and education. Opening up discussion to different thought risks losing domination of these industries, so I can understand the (Robin DiAngelo voice) fragility among journalists and professors to ideological diversity. However, I'm sure liberals would agree that the military and police force could benefit from ideological diversity since they are dominated by conservatives.

Conservatives might be okay with collateral damage, waterboarding, and "leaning forward" because the ends justify the means when it comes to war. Liberals in the military would push back against this, and I think that is a good thing, but would people be willing to make these trade offs to achieve ideological equilibrium?

I tried to think of institutions lacking ideological diversity and this is what I came up with:

Liberal leaning

- media/journalism

- higher education

- elementary/secondary education

- Hollywood/art

- military

- police

- Wall Street

- entrepreneurs

My gut instinct is that the tech sector leans left. While it is a business, Google's reaction to the James Damore memo suggests that liberal ideology is the dominant view. But maybe they're an outlier.

II.

So back to the Rawls experiment. If you could design a world, would you want ideological equality in all major institutions or would you keep them the way they are, assuming that you would be born into this world with a predetermined, unfixed ideology that you do not choose. You might be a liberal police chief or a conservative humanities professor, surrounded by people who oppose your beliefs.

A good argument in favor of the status quo is that there already is an ideological equilibrium. Institutions can be dominated by ideology, as long as there is a balance among the institutions rather than within the institutions. So if you have conservatives in the military, police, and on Wall Street, they are balanced by liberals in universities, major news organizations, and in the classroom.

A good argument against that idea is that not all major institutions are the same. In fact, I'd say that the military and police and quite powerful, as they possess the threat of force. Wall Street is exceptionally strong as well, as we saw during the 2008 financial crisis.

While the media is powerful, it's becoming more diffuse and could never match the threat of a rogue police state. So while the number of major industries might be in balance, I think the power leans in the direction of conservatives.

Also, a lot of the recent research I read shows that echo chambers breed extremism. These institutions become feedback loops where the more orthodox they get, the more hostile they become to outside points of view, which leads the few dissenters leaving, which leads to more orthodoxy. So keeping things status quo means that these institutions are going to get more extreme and dangerous.

III.

So if I had to choose, I would want ideological equilibrium.( I don't have skin in the game, since my views of rationalism and constitutional localism are not at risk of losing any power. We don't have any. We are minorities in all institutions.) But I think putting a check on power is something we can all agree on.

As much as I preach for ideological diversity in higher education, after working on this post I have come to have my doubts. If I'm a liberal, I'm not sure I would give up my dominance without assurance that there was more ideological diversity in the military (technically, all you need is a liberal in the White House, as they command the military).

But we don't have to operate in Rawls' hypothetical world-building. We can build a system based on the critical-theory left's ideas of equity. It involves a level of coercion I am not comfortable with, and it seems like it would be unpopular, but if you framed it in terms of a tit-for-tat trade, you might have something.

In a previous post, I argued that voting for extreme candidates ensures gridlock and pushes power to the local level. But there is another type of gridlock. It isn't just extreme left vs. extreme right. There can also be extreme left vs. moderate left, and extreme right vs. moderate right.

I think that's what we used to have and it seems like more got done. If this holds true for the private sector, then ideological diversity within institutions is a more efficient system.

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

When Fatalism Means Freedom

I responded to a friend's Facebook post about depression. I didn't do a good job of articulating a response so I'm going to try to do that here.

The Happiness Curve shows that happiness is highest in our early 20s, goes down each year, bottoms out around 45-50, and goes up each year after that.

I think about this whenever I am stressed. It is easy to blame my problems on something fundamentally flawed about myself (introversion, neuroticism), or on my unique situation (kids, finances). But the happiness research reminds me that I'm not unique; I'm just a person in his late 30s on the down slope of the curve.

In other words, this is supposed to happen.