I responded to a friend's Facebook post about depression. I didn't do a good job of articulating a response so I'm going to try to do that here.

The Happiness Curve shows that happiness is highest in our early 20s, goes down each year, bottoms out around 45-50, and goes up each year after that.

I think about this whenever I am stressed. It is easy to blame my problems on something fundamentally flawed about myself (introversion, neuroticism), or on my unique situation (kids, finances). But the happiness research reminds me that I'm not unique; I'm just a person in his late 30s on the down slope of the curve.

In other words, this is supposed to happen.

Whatever problems seem to cause your depression—loneliness, work, money, etc.—don't just disappear once you turn 56. And yet, everyone seems to get happier at that age. Even people in their 80s and 90s, in the worst physical health of their lives, are happier than ever (a good counter argument is that this could be survivorship bias: the least happy people die by this age and are no longer counted in the data).

As a non-theist, I don't believe in fatalism as divine intervention. But I do believe that evolutionary factors and cultural forces shape my behavior beyond my sovereign control of it.

And yet, this makes me happy.

I find liberty in knowing that I don't have a whole lot of control over my well being and that it is going to get better. Maybe I like knowing that I won't have to do anything to be happier, other than wait to turn 56.

I remember reading Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus in which he concludes, "One must imagine Sisyphus happy." I never understood that essay, but I think I do now. There is a certain freedom in resigning myself to the understanding that my life is just following a script and I know it has a happy ending.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Wednesday, August 28, 2019

Monday, August 26, 2019

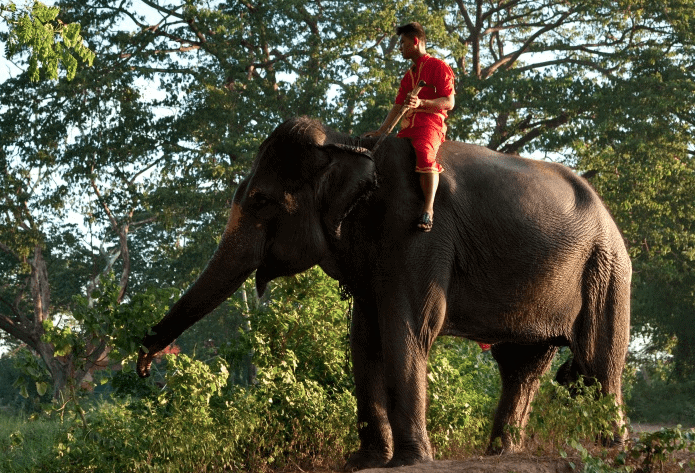

Talking to the Elephant

When trying to persuade someone who doesn't think like you, Jonathan Haidt said it's important to "talk to the elephant." He uses the elephant/rider metaphor to explain our subconscious/intuitive mind as an elephant, and the rider as our rational consciousness. The elephant moves where it wants but rider can try to steer it, although not always successfully.

Haidt's point is that people don't think logically, so your argument should speak to their emotional/intuitive instincts.

I wrote a post about how liberals should look for a reason for conservatives to use a transgender person's preferred pronoun, because "standing up for the oppressed" doesn't speak to their elephant. I only recently realized that Scott Alexander already made a good argument for this.

He goes through a really long post that eventually leads to this conclusion:

- It's probably not "true" that a biological male can be a woman, however;

- Transgender persons are at very high risk of suicide;

- Calling a transgender person their preferred pronoun can greatly reduce this risk, therefore;

- The benefits of using a transgender person's pronoun outweigh the costs of saying something he doesn't believe to be true.

In this instance, Alexander makes an appeal to common humanity identity politics. Reducing suicide is something we can all agree is a good thing; it transcends tribal partisanship. It's an argument that has the best chance of working with conservatives and other non-progressives because it speaks to their emotions and avoids tribal signaling.

Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Obedience > Creativity

On the penultimate day of my son's summer camp, parents are invited to take part in "family night". Part of the evening involves each age group performing a song for the families in attendance.

I was following around my two year old daughter, who cannot sit still, as she explored the camp. As we walked away from the picnic area where the performances were going on, we found an octagonal shaped platform, about 10 feet across, surrounded by an octagonal shaped fence, about three feet high.

Suddenly, a group of kids who had finished their performance rushed over, hopped the octagonal fence, and began playing a game they had clearly been taught over the course of the week. Although the game was supposed to involve a ball, having no ball, they improvised and used one kid's shoe.

Meanwhile, another group of kids was giving their performance as the families continued to watch. As the group of kids playing the game became louder and more intense, a camp director eventually came over, made them stop, and told them to return to the picnic area.

I keep thinking about this story for several reasons. It reminds me of the research into "nurturing" versus "strict" parenting styles. Apparently, whichever one chooses is a very strong predictor of how they vote.

One of the questions the researchers would ask is if you think it's more important for a child to be creative or obedient. Creative respondents tended to be liberal voters and were given the "nurturing" label; obedient respondents tended to be conservative voters and were given the "strict parent" label.

In the story I told, almost any adult would agree with the camp director's decision to end the game and make the kids return to the picnic area (in case I wasn't clear, they were never given permission to play and were supposed to be seated the entire time). The pro arguments are that it is distracting to the families trying to listen to the other students' songs and unfair to the kids who had practiced their routine and sat through the earlier performances.

However, my guess is that, given the chance, almost all campers would have preferred to play than to give their performance. So who is the performance really for: the campers or their families?

In siding the camp director, we choose obedience over creativity. When asked, progressive parents will say they prefer a creative child to an obedient one. But in practice, I think they are more likely to do the latter and scold the group of campers, who had created their own game, for not sitting quietly at their picnic table.

Peter Gray writes frequently about the need for unstructured, unsupervised play. But as a society, we continue to move further away from that ideal, even the parents who might think of themselves as "nurturing."

Monday, August 12, 2019

Want Libertarianism? Vote Democrat (or Republican)

In The Joy of Federalism, Frank Foer writes about how states have passed legislation in areas the federal government has made no progress.

On a message board, I saw a libertarian-leaning poster write about how he doesn't vote for a party, he votes for gridlock. He doesn't trust either of the major parties, so he favors a situation in which neither one has power.

It seems that the outgrowth of this strategy is that it pushes power downward to the local level (it feels unjust that us taxpayers are paying the legislative body all this money to not pass legislation).

All of this makes me wonder: is voting for libertarian candidates the most effective strategy for libertarian voters? Or is it voting for the most extreme, uncompromising candidates in the minority party, thus ensuring gridlock?

"New York's attorney general Eliot Spitzer, declaring himself a "fervent federalist," is using state regulations to prosecute corporate abuses that George W. Bush's Department of Justice won't touch. While the federal minimum wage hasn't budged since the middle of the Clinton era, 13 (mostly blue) states and the District of Columbia have hiked their local wage floors in the intervening years. After Bush severely restricted federal stem cell research, California's voters passed an initiative pouring $3 billion into laboratories for that very purpose, and initiatives are under way in at least a dozen other states."Bill Bishop believes that congressional gridlock is what creates the conditions for this type of federalism to flourish.

On a message board, I saw a libertarian-leaning poster write about how he doesn't vote for a party, he votes for gridlock. He doesn't trust either of the major parties, so he favors a situation in which neither one has power.

It seems that the outgrowth of this strategy is that it pushes power downward to the local level (it feels unjust that us taxpayers are paying the legislative body all this money to not pass legislation).

All of this makes me wonder: is voting for libertarian candidates the most effective strategy for libertarian voters? Or is it voting for the most extreme, uncompromising candidates in the minority party, thus ensuring gridlock?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)