I really enjoyed the Jonathan Rauch column I reviewed because it gave an answer to my favorite question: what caused the decades-long decline of social capital? All forms of civic engagement—working for a political party, going to church, volunteering for Kiwanis, even bowling—require trust in an institution, in some type of structure that asks for buy-in from its participants.

Even bowling in a league requires people to become a "member" of the league and follow its rules.

The Atlantic ran a story about how the end of the landline is affecting modern families. The more telling tale is the rise of viewing devices; each house having multiple flat screens, smartphones, tablets, and laptops for each family member to watch their own show.

TV monoculture is over because producers no longer have to create shows that appeal to everyone. Family viewing—itself an institution, featuring two dictators (the parents) determining what is best for the proletariat (the kids)—is a thing of the past. Each member has their own device and can watch their own type of show.

The atomization of the family unit is moving people toward more private and individual lives, and away from the structures that invite people into public life, or even the family room.

Helicopter Parenting

The authors of The Coddling of the American Mind, the author of iGen, and websites like Let Grow blame a lot of the problems with today's youth--like anxiety and depression--on helicopter parenting. They say it is important for kids to have unstructured unsupervised play and parents are not allowing that.

But what if it's not that simple? What if kids are leaving the house less because they don't want to, because they like the quality of entertainment at their disposal and don't feel compelled to leave the house to make new friends of have social interactions with current ones?

The average family is also smaller, so there is less experience with compromise. They don't have the necessary experience for negotiating public life and working through conflict.

Social Diabetes

Here's what I don't get: why does it feel good to do something that is bad for us?

Why does it feel better to read a book on philosophy in a quiet room than to attend weekly Mass?

Why do I enjoy sitting on my living room couch, scrolling through my Twitter timeline, putting a show for my son on our TV, and putting Netflix on our laptop for my daughter, as opposed to picking something we all can watch?

Why do I write blog posts about how disappointing I find our politicians to be instead of volunteering for the campaign of someone I believe can do better?

Eating I understand. Sugar is rare in the natural world, and our bodies need it in small amounts, so we have adapted traits that tell us to load up when something tastes sweet, knowing we might not find it again for weeks.

We understand that high levels of sugar are bad for us and are at least working on it. I feel like we understand the harmful effects of pulling away from public life, but we're not too concerned about it. There are public campaigns about opioid abuse and suicide, but not about their root causes: loneliness and isolation.

People choose personalization over sharing and compromise when given the choice. We choose to unite over a common enemy rather than work on a common project. The upshot is that this is terrible for society. It brings out the worst in our tribal impulses. We have no experience sharing in our personal life and expect democracy and society to be the same.

We're all coming up with Type II social diabetes but we're okay with the tradeoff because the saccharine personalization of entertainment tastes so damn good.

It could be that we've just never had the opportunity for personalization in human history, so we don't know how to deal with its externalities. But I'm growing less confident that we'll get to a point where we realize how bad this is for all of us and actually do something about it.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Best of 2019

Below are the best things I read or listened to in 2019.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

Jonathan Rauch

"In many respects, institutions are enemies of tribalism, at least in the context of a liberal society. By definition, they bring people together for joint effort on common projects, which builds community. They also socialize individuals and transmit knowledge and norms across generations. Because they are durable (or try to be), they tend to take a longer view and discourage behavior that considers only self-interest in the very short term...

"The more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."

Jonathan Rauch and Ray La Raja

"Turnout in primaries is notoriously paltry, and those who do show up are more partisan, more ideological, and more polarized than general-election voters or the general population. They are also wealthier, better educated, and older.”

"When party insiders evaluate candidates, they think about appealing to overworked laborers, harried parents, struggling students, less politicized moderates, and others who do not show up on primary day—but whose support the party will need to win the general election and then to govern. Reducing the influence of party professionals has, as Shafer and Wagner observe, amplified the voices of ideological activists at the expense of rank-and-file voters."

Ross Douthat

"[W]e should subdivide the “despair” problem into distinct categories: A drug crisis driven by the spread of heroin and fentanyl which requires a drug policy solution; a surge in suicides and depression and heavy drinking among middle-aged working-class whites to which economic policy might offer answers; and an increase in depression and suicide generally, and among young people especially, that has more mysterious causes (social media? secularization?) and might only yield to a psychological and spiritual response...

"But at the same time the simultaneity of the different self-destroying trends is a brute fact of American life. And that simultaneity does not feel like just a coincidence, just correlation without entanglement — especially when you include other indicators, collapsing birthrates and declining marriage rates and decaying social trust, that all suggest a society suffering a meaning deficit, a loss of purpose and optimism and direction, a gently dehumanizing drift."

Peter Beinart

“There is a secrecy “heuristic”—a mental shortcut that helps people make judgments. “People weigh secret information more heavily than public information when making decisions,” they wrote. A 2004 dissertation on jury behavior found a similar tendency. When judges told jurors to disregard certain information—once it was deemed secret—the jurors gave it more weight.

"While it’s unlikely Trump has heard of the secrecy heuristic, his comments about murder on Fifth Avenue suggest he grasps it instinctively. He recognizes that people accord less weight to information that nobody bothers to conceal. If shooting someone were that big a deal, the reasoning goes, Trump wouldn’t do it in full public view.

"By openly asking Ukraine and China to investigate a political rival, Trump expressed confidence that he’s doing nothing wrong. And while one might think the majority of Americans would view Trump’s confidence as an outrageous sham, academic evidence suggests that con men can be surprisingly difficult to unmask."This article is what made me think that Trump truly has something to hide in his tax returns. It's the only thing he keeps secret, which is probably why I give it more weight. But given what we know about Trump, it's probably less nefarious and more embarrassing. My guess is that he doesn't have as much money as he wants people to think.

"The Ideological Turing Test: How to Be Less Wrong"

Charles Chu

Charles Chu

"What we believe as ‘true’ today is just a small blade of grass in a miles-wide graveyard of ideas.

"Much of what we believe today is doomed to join other infamous dead theories like Lamarckism (“Giraffes have long necks because they used them a lot.”), bloodletting (“Let me put a leech on your forehead. It’ll cure your allergies. I promise.”), and phrenology (“I’m better than you because I have a bigger head.”)...

"Bryan Caplan says that I should understand my opponents’ ideas so well that they can’t tell the difference between what I am saying and what they believe."

A guide to the most—and least—politically open-minded counties in America"

Amanda Ripley, Rekha Tenjarla, Angla Y. He

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

John Wood Jr.

"Klein worries that the solutions to the problems that concern Haidt and Lukianoff are also wicked in precisely the opposite direction. Civility and moderation, desirable qualities for political discourse and decision making, can numb us to the imperative of social change.

"Klein argues that successful activism has a history of making people uncomfortable, who would otherwise simply ignore injustice. 'Confrontation is unpopular, and often necessary, in part to get people to see things they don’t want to see.'

"We must realize that the maintenance of dignity in activism does not require the abandonment of fervor."This too sparked a blog post of mine.

Podcasts

The Rewatchables: The Shining featuring Bill Simmons, Sean Fennessey, and Chris Ryan

The Ezra Klein Show: Michael Lewis reads my mind

The Ezra Klein Show: Matt Yglesias and Jenny Schuetz solve the housing crisis

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"As it took its first baby steps, the Blue Tribe started asking itself “Who am I? What defines me?”, trying to figure out how it conceived of itself. New Atheism had an answer – “You are the people who aren’t blinded by fundamentalism” – and for a while the tribe toyed with accepting it. During the Bush administration, with all its struggles over Radical Islam and Intelligent Design and Faith-Based Charity, this seemed like it might be a reasonable answer. The atheist movement and the network of journalists/academics/pundits/operatives who made up the tribe’s core started drifting closer together.

Gradually the Blue Tribe got a little bit more self-awareness and realized this was not a great idea. Their coalition contained too many Catholic Latinos, too many Muslim Arabs, too many Baptist African-Americans. Remember that in 2008, “what if all the Hispanic people end up going Republican?” was considered a major and plausible concern. It became somewhat less amenable to New Atheism’s answer to its identity question – but absent a better one, the New Atheists continued to wield some social power.

Between 2008 and 2016, two things happened. First, Barack Obama replaced George W. Bush as president. Second, Ferguson. The Blue Tribe kept posing its same identity question: “Who am I? What defines me?”, and now Black Lives Matter gave them an answer they liked better “You are the people who aren’t blinded by sexism and racism.”"BOOK REVIEW: THE SECRET OF OUR SUCCESS"

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

"Henrich discusses pregnancy taboos in Fiji; pregnant women are banned from eating sharks. Sure enough, these sharks contain chemicals that can cause birth defects. The women didn’t really know why they weren’t eating the sharks, but when anthropologists demanded a reason, they eventually decided it was because their babies would be born with shark skin rather than human skin."One of the reasons I like Scott is the he is critical of his own beliefs. This book is actually an argument against rationalism. The irrational idea that eating shark will give your baby shark skin is an idea that survived for so long that it must have a reason, however irrational it appears.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

"If you were to put a gun to my head and force me to break down the importance of various factors in contributing to wage decoupling, it would look something like (warning: very low confidence!) this:Shameless Self-love

– Inflation miscalculations: 35%

– Wages vs. total compensation: 10%

– Increasing labor vs. capital inequality: 15%

—- (Because of automation: 7.5%)

—- (Because of policy: 7.5%)

– Increasing wage inequality: 40%

—- (Because of deunionization: 10%)

—- (Because of policies permitting high executive salaries: 20%)

—- (Because of globalization and automation: 10%)"

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

A National Network of Community

One pattern Tyler Cowen observes in The Complacent Class is the growing reluctance of Americans to switch jobs and move to another state.

A common response is that poor people don't have the financial means to move, even if it means a better job. I'm not sure I entirely buy that. At the very least, it's only telling part of the story.

So what is keeping low-wage workers in low-productivity towns?

Personally, the number one reason I don't move is that my family is here and I don't like meeting new people. I have a very narrow window for people I'm not related to that I actually like spending time with. But if I knew MY TYPE OF PEOPLE would be in a new community where I have a job opportunity, I might consider moving.

That is why I wonder how much the decline of attendance in national institutions have had on geographic mobility. There has been a rise in independent protestant and Evangelical churches over the past 30 years and a commensurate decline in Catholic, Episcopal, Southern Baptist and United Methodist churches.

The advantage of having a national brand of religion is that you can be sure a community of like-minded believers will be waiting for you when you move to a new area. The same goes for Rotary International or any other civic organization.

When institutions are localized, it stymies the incentive to move somewhere different where you might not feel welcomed. Having a social infrastructure in place, where you already have some type of membership, at least gets you a foot in the door.

If family is what keeps me rooted, community is what can lure me away. A national network of ideologically-driven colleges and universities might be able to Make America Mobile Again.

This article traces it a little better and finds a similar conclusion.

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Strong institutions or inclusive parties?

I.

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

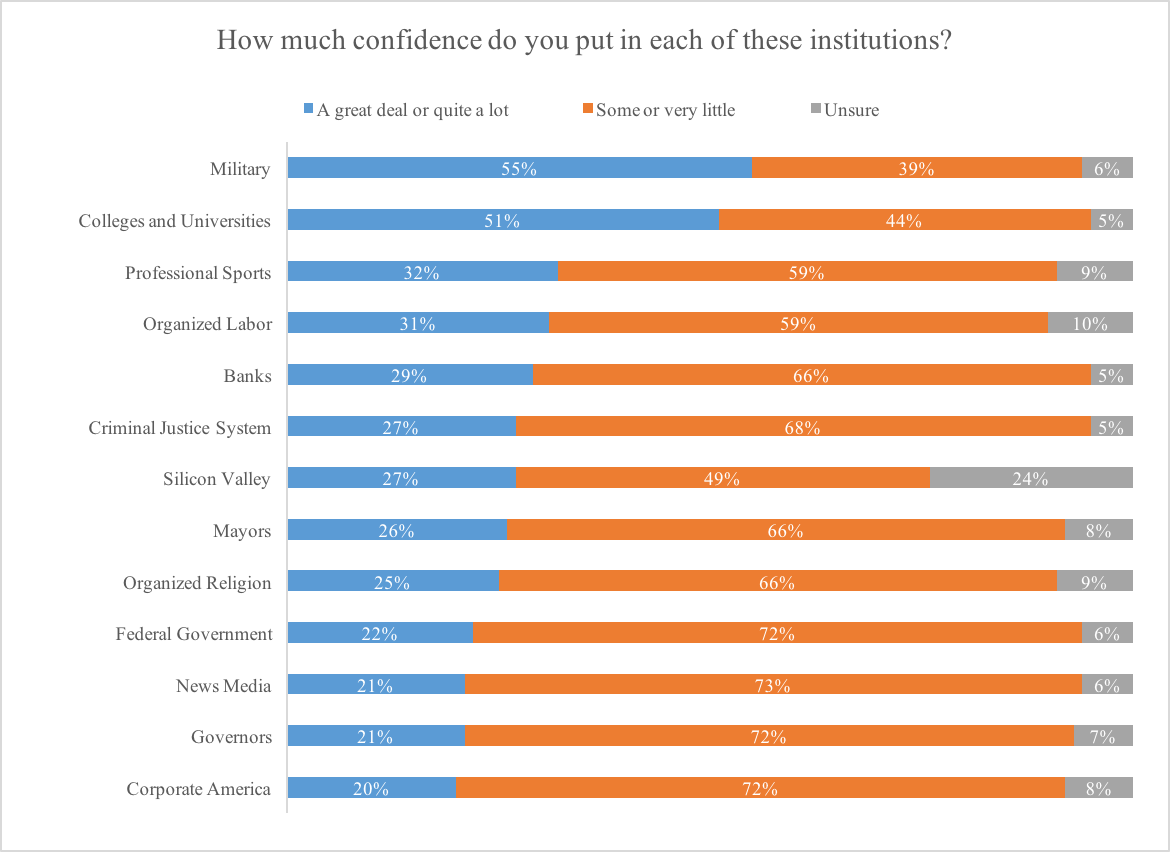

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

"Paradoxically, partisanship has never been stronger, but the party organizations have never been weaker — and this is not a paradox at all. When they had the capacity to do so, party organizations engaged citizens in volunteer work, local party clubs, and social events, giving ordinary people a sense of political engagement that merely voting or writing a check cannot provide. Until they lost the power to do so, they road-tested and vetted political candidates, screening out incompetents, sociopaths, and those with no interest in governing. When they could, they used incentives like jobs, money, and protection from primary challenges to get legislators to work together and accept tough compromises. Perversely, the weakening of parties as organizations has led individuals to coalesce instead around parties as brands, turning organizational politics into identity politics.

To put the point another way, the more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."And later:

"Getting traction against affective polarization and tribalism will require some direct measures, such as civic bridge-building. Even more, it will require indirect measures, such as strengthening institutions like unions, civic clubs, political-party organizations, civics education, and others. Above all, it will require re-norming: rediscovering and recommitting to virtues like lawfulness and truthfulness and forbearance and compromise."I want to believe that strong parties can build social capital and strengthen communities. Can we have that without pushing outside candidates to the margins?

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

- Strong institutions might allay our country's current tribal crisis, but I'd really like to research this idea more.

- If the result of weakening political parties is that they make room for outside candidates who otherwise would have run as a third party, I think that is a good thing.

- I'm not convinced that we can revive the Democrat and Republican parties to their 1950s strength. We (meaning Millenials and Gen Z) might have to put our faith in new institutions.

- If colleges follow the Jon Haidt model and be transparent about their ideology, people will choose whichever matches their preference. Investment in more colleges, especially in this model, might lead to strong institutions that people trust, which will build loyalty to the institution that can then reduce tribalism.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/47775331/partisanship2__1_.0.0.jpg)