The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Friday, March 27, 2020

UBI(A): Universal Broadband Internet Access

One thing made clear from all this homeschooling is the need for internet access. On an Econtalk episode with Tyler Cowen, he and Russ Roberts discuss how social distancing might change society. We might find it more efficient to continue to work and learn remotely. If this trend continues, that means that guaranteeing public education for all children would have to guarantee internet access.

According to the FCC, 6 percent of US households do not have broadband access. That seems small (this says says 60 million, which would be 18 percent), but I can already give anecdotal stories from my father who teaches a community college course to working adults who never completed high school. One of his students has to go to McDonald's to send email. Now that restaurants are closed, I don't know what he's doing.

So why not subsidize?

This article in Reason shows that Lifeline, a federal program that subsidizes telephone and broadband internet service for low-income Americans, has been handing out subsidies to dead people. So efficiency and accountability might be an issue. One critique of Lifeline is that it offers the choice of a smartphone (remember Obama phones?) or internet access and most people choose the former. It's a harder sell to tell people that cell phones are a human right.

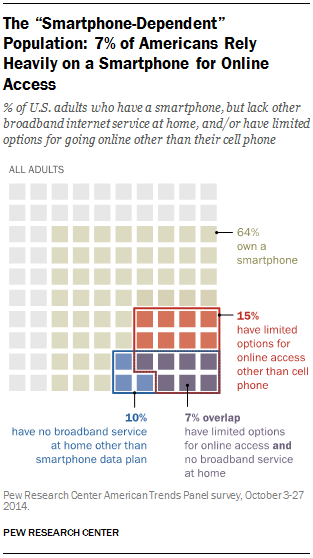

So is internet access even a problem? Here's some good news: Pew shows that internet usage is up dramatically. Even 66 percent of citizens without a high school diploma are on the internet. However, many of them are dependent on their smartphone for access, which isn't conducive to things like online learning.

This report shows that "19% of Americans rely to some degree on a smartphone for accessing online services and information and for staying connected to the world around them — either because they lack broadband at home, or because they have few options for online access other than their cell phone." (this might be where that earlier link gets their 18 percent number from.)

So even if we hand out Chromebooks to every student in America, an unacceptable number of them (roughly one out of five) won't be able to log into their teacher's learning portal.

It isn't just about affordability. Many rural communities don't even have the option to purchase broadband. It's often too expensive, meaning too little ROI, for private companies to build in rural areas. They get more money by setting up shop in denser, wealthier neighborhoods and profiting off that sweet monopoly money.

A growing trend is local communities building their own Internet networks. This interactive map shows you where.

Reason looked at a University of Pennsylvania study which examined 20 city-owned broadband networks around the country whose profitability could be gauged, 11 of which are operating at a loss.

They also link to an interactive map of 200 municipal networks showing that 14 have failed while another 50 remain mired in over $1 million in debt. In total that's 64 out of 200, so ... most of them work just fine?

I get it, libertarian-leaning Reason, there will be efficiency problems if we choose government over private business. But the status quo is leaving a lot of people out in the (virtual) cold and, if you believe in meritocracy, these people should be given a chance to prove their worth. Especially when the market is not providing them with that chance.

Instead of framing broadband internet access as an argument about it being a right vs. a luxury, it should be viewed as an extension of education, pre market and post market (an idea explained in my review of The Third Pillar).

Better yet, it should be thought of as an investment in human capital. We should make it easy for people to apply for jobs online, take online courses, become auto didacts via edX, or, hell, even Wikipedia.

We guarantee everyone a basic education, which doesn't seem to be doing much these days. At the very least we should guarantee them the chance to compete with an increasingly online world.

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

I was wrong about Trump

I've written many regretful blog posts here. Sometimes I write things that I disagree with after the fact. Sometimes I make forecasts that are proven wrong, such as my hopeful post about Trump from 2016.

I wrote:

In my post, I pulled this quote from FiveThirtyEight:

I also delivered this gem:

I wrote:

"Because now that he's president, America is his brand. He cares a great deal what other people think of him (almost to a fault ... no, definitely to a fault) and will want to make decisions based on how the country will look, not just himself."What I didn't predict was how much he would hitch his wagon to the stock market. Now we find ourselves in a predicament where he has to choose between supporting the stock market (ending social distancing and reopening businesses) and doing the right thing (continuing social distancing and saving as many lives as possible). He appears to be favoring the former.

In my post, I pulled this quote from FiveThirtyEight:

"Many of Trump’s major economic promises, however, would require cooperation with Congress and/or the Supreme Court. So repealing Obamacare, cutting taxes and building his infamous wall on the Mexican border — Trump couldn’t do that unilaterally."I didn't foresee how much the GOP would fall in line for fear of Trump turning his base against them. Like Trump, when the GOP also chose selfishly when having to choose between upholding conservative principles (free market, free trade, not putting kids in cages) and compromising those principles to stay in power.

I also delivered this gem:

"Now that Trump is president, if rejecting open trade and closing our borders to immigrants is as disastrous as most economists agree it will be, that gives voters empirical evidence that these ideas do not work for the next election."His policies have not done much to derail the economy. It's hummed along despite his interference. You can point out specific instances that have been negative, but in the aggregate employment and production have been just fine.

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

An update on my Sacrifices post

There are a few obvious reasons people are ignoring social distancing protocol and I didn't want to make it seem that "a lack of opportunities for heroism" is the best I could come up with.

First, it's easy to forget that many people aren't following the news as much as I am. It is quite likely that the young people on spring break read that they are at low risk for dying from infection ... and simply stopped reading after that.

They probably never considered the fact that they could be asymptomatic and pass the virus on to someone who could die from it. So simple ignorance is a very probable explanation.

Second, the parents in my generation might not be considering the fact that staying home is a bigger sacrifice for young people than it is for us. Now that schools have closed, my kids are already at home. I've been told to telecommute to work. So my biggest responsibilities, work and parenthood, have made the decision to quarantine for me.

For young people, for whom socialization is a big part of their life, staying under quarantine is a big sacrifice. Most college students don't work and are childless. I think it's easy to forget about this.

Finally, this is something I read years ago that I'm going to try to explain but I'll probably get something wrong. In a nutshell: The secondary effects of passing the virus on don't feel as real to us.

In Moral Tribes, Joshua Greene uses the philosophical trolley problem to explain how the mind works.

Greene found that the results changed a bit from the original scenario, with more people willing to be okay with the physical act of commission that leads to a bystander's death once the secondary track is added.

It seems that adding these secondary effects made the deaths less real to some people. Likewise, the idea of catching a virus and unknowingly passing it on to someone who dies from it, someone you never know, feels less urgent.

It's not lost on me that, in the trolley scenario, you get to save five lives; an act of heroism.

First, it's easy to forget that many people aren't following the news as much as I am. It is quite likely that the young people on spring break read that they are at low risk for dying from infection ... and simply stopped reading after that.

They probably never considered the fact that they could be asymptomatic and pass the virus on to someone who could die from it. So simple ignorance is a very probable explanation.

Second, the parents in my generation might not be considering the fact that staying home is a bigger sacrifice for young people than it is for us. Now that schools have closed, my kids are already at home. I've been told to telecommute to work. So my biggest responsibilities, work and parenthood, have made the decision to quarantine for me.

For young people, for whom socialization is a big part of their life, staying under quarantine is a big sacrifice. Most college students don't work and are childless. I think it's easy to forget about this.

Finally, this is something I read years ago that I'm going to try to explain but I'll probably get something wrong. In a nutshell: The secondary effects of passing the virus on don't feel as real to us.

In Moral Tribes, Joshua Greene uses the philosophical trolley problem to explain how the mind works.

"A runaway trolley is about to run over and kill five people. In the switch dilemma one can save them by hitting a switch that will divert the trolley onto a side-track, where it will kill only one person. In the footbridge dilemma one can save them by pushing someone off a footbridge and into the trolley’s path, killing him, but stopping the trolley. Most people approve of the five-for-one tradeoff in the switch dilemma, but not in the footbridge dilemma."Greene found that subjects' responses changed when they added in the loop variant as well as the obstacle/push collide variant.

"As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people and you can divert it onto a secondary track. However, in this variant the secondary track later rejoins the main track, so diverting the trolley still leaves it on a track which leads to the five people. But, the person on the secondary track is a fat person who, when he is killed by the trolley, will stop it from continuing on to the five people.

The only physical difference here is the addition of an extra piece of track."Here is a figure that may help.

Greene found that the results changed a bit from the original scenario, with more people willing to be okay with the physical act of commission that leads to a bystander's death once the secondary track is added.

It seems that adding these secondary effects made the deaths less real to some people. Likewise, the idea of catching a virus and unknowingly passing it on to someone who dies from it, someone you never know, feels less urgent.

It's not lost on me that, in the trolley scenario, you get to save five lives; an act of heroism.

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Sufficiently-Demanding Sacrifices

The above tweet from Elizabeth Bruenig is her take on the film Joker. I think her line about "a lack of opportunities for heroism" best gets at what the film and its cultural impact are about.

I haven't thought about that tweet until recently when I began to see content on Twitter responding to coronavirus like this:

There are numerous other instances of people heading out to bars and other crowded spaces, very much in spite of CDC recommendations, which has sparked responses like this:

I know there is less patriotism and civic trust now than in the 1940s but I can't help but think that the difference in the public response between WWII and coronavirus has something to do with what we are asking people to sacrifice.

I read somewhere that the religion with the most loyal followers will be the one that demands the most from its adherents. It should not be a surprise that suicide bombers abstain from alcohol and cover their women head to toe.

The people heading out to bars are people who are probably not going to die from COVID-19. We're not asking them to save their own lives, we're asking them to make a sacrifice for others. Is the problem that the sacrifice is demanding too little? After all, there is nothing heroic about staying home and watching Netflix.

Is the problem that the risk of exposure is actually enticing to these young men, since most of us have never had a rite of passage to prove our manhood?

Instead of paternalistic lecturing, I wonder if more people would listen if this was framed as an opportunity for heroism.

We need healthy young men to deliver groceries to the elderly, the immunocompromised, and those at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 who cannot leave their homes. We need adults without children to volunteer to watch the kids of doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals so they can go to work and keep our hospitals operating at maximum capacity.

We need you to be leaders in our communities because no one else is going to do it. We need heroes because the stakes are so high.

There are certainly people who are going to do what they want, no matter how you frame the conversation. Just as I'm sure there were students who did not want to give up their class ring during WWII. But there might be enough people willing to listen to make a difference.

I haven't thought about that tweet until recently when I began to see content on Twitter responding to coronavirus like this:

Downtown Nashville is undefeated. pic.twitter.com/BFIOzukFct— Janna Abraham (@SportsPundette) March 15, 2020

There are numerous other instances of people heading out to bars and other crowded spaces, very much in spite of CDC recommendations, which has sparked responses like this:

I remember talking to a nun at a college where I used to work. She was a student there during WWII. She talked about how they gave up their class rings because the country needed the metal for the war efforts. She described it as a sacrifice people were happy to make.Greatest Generation: Came together and laid down their lives to defeat Hitler in WWII.— Sean Kent (@seankent) March 15, 2020

Current Genrations: Hoarding toilet paper and refusing to stay home and watch Netflix so people don’t die.

I know there is less patriotism and civic trust now than in the 1940s but I can't help but think that the difference in the public response between WWII and coronavirus has something to do with what we are asking people to sacrifice.

I read somewhere that the religion with the most loyal followers will be the one that demands the most from its adherents. It should not be a surprise that suicide bombers abstain from alcohol and cover their women head to toe.

The people heading out to bars are people who are probably not going to die from COVID-19. We're not asking them to save their own lives, we're asking them to make a sacrifice for others. Is the problem that the sacrifice is demanding too little? After all, there is nothing heroic about staying home and watching Netflix.

Is the problem that the risk of exposure is actually enticing to these young men, since most of us have never had a rite of passage to prove our manhood?

Instead of paternalistic lecturing, I wonder if more people would listen if this was framed as an opportunity for heroism.

We need healthy young men to deliver groceries to the elderly, the immunocompromised, and those at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 who cannot leave their homes. We need adults without children to volunteer to watch the kids of doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals so they can go to work and keep our hospitals operating at maximum capacity.

We need you to be leaders in our communities because no one else is going to do it. We need heroes because the stakes are so high.

There are certainly people who are going to do what they want, no matter how you frame the conversation. Just as I'm sure there were students who did not want to give up their class ring during WWII. But there might be enough people willing to listen to make a difference.

Monday, March 16, 2020

When to Worry

Here is something I get stuck on. Letgrow.org has a mission of promoting free play among youth. They rally against the stigma that children are in constant danger, citing statistics that show how rare child abduction is. I believe in this.

I also believe in the Black Swanism of Nassim Taleb. The abduction of my children, however low a probability, is a tail risk: unlikely but incredibly damaging. So am I right to panic and over-prepare for such a scenario?

I guess the answer is: it depends. One of the most interesting reads I've come across is titled "Is Sunscreen the New Margarine?" The article posits that using sunscreen to prevent skin cancer is an overreaction that blocks vitamin D, thus increasing the risk of heart disease. The author believes that this trade off is actually worse.

This is like the study showing that any safety that comes with the protection of an oversized SUV is wiped out by its likelihood of rolling over.

I guess the answer to my dilemma is that it is okay to panic in preparation of a tail risk as long as the panic does not lead to an externality that is worse than the original thing I'm worried about.

For corona virus panic, social distancing, hand washing, and sanitizing have no major externalities and make sense no matter how small the risk of contracting illness. (I'm willing to admit that long-term isolation from quarantining can have damaging psychological effects.)

However, stocking up on masks and checking into the hospital after every cough are examples of panic that harm the supply of resources for people who really need it. This is an externality that overwhelms hospitals beyond capacity and actually makes things worse.

So there is good panic and bad panic; "better safe than sorry" panic with little trade off, and panic that leads to outcomes worse than if you had just done nothing.

Getting back to my original dilemma: I don't have a good way of measuring the trade offs between abduction prevention and cultivating mentally healthy children. Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have a lot of good research into the increase in anxiety, depression, and suicide attempts that correlate, somewhat, with helicopter parenting.

But I still don't feel confident about taking a side. Obviously if you gave me the option of my children being abducted or them having depression and suicidal ideations, I would take the latter. The damage is easy to compare between the two scenarios, but not the level of risk.

Kids being deprived social skills and the natural learning that comes from unsupervised and unstructured play seems pretty likely to increase mental health issues in their future. But lax supervision is still unlikely to lead to abduction, which is rare no matter what you do.

But it's not an apples to apples comparison. My children can only be abducted if I'm not around, so it's something I have a lot of control over. But there are so many factors that go into mental health, an area we don't totally understand to begin with. Giving my son a little more freedom might nudge him in a healthier direction but it still might not be enough to prevent his depression when so many other factors are brought in.

I started writing this blog post with the hope that I would find a rational solution but I'm still unsatisfied. All I can do is manage my panic as appropriate and be mindful that my actions aren't actually making things worse.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)