Short takes are supposed to be about new information I've read that confirms or disconfirms my prior beliefs. Lately I feel they have been doing too much confirming so I want to focus and things I've read that make me less confident in my beliefs.

I've complained about a lot of things that schools are doing under the Critical Race Theory umbrella. Because of the writing of Matt Yglesias, I now am a big supporter of culturally relevant pedagogy, which has empirical support in reducing inequity. If this makes me a social justice warrior then slap some pronouns in my bio and call me an ally.

Although I've never directly criticized The 1619 Project on its merits, I haven't framed it in the most flattering terms. At the urging of another Yglesias post, I read Hannah-Jones' lead essay and was struck by how patriotic it was. Even if some of the foundations for the argument are shaky, if reading this causes African Americans to have warmer feelings about their country I think that is a good thing.

I've also become slightly less confident in coalition building. Antiwokes, like James Lindsay, and conservative Christians, like Chris Rufo, have worked together to ban CRT in certain school districts. Now some of these school districts using these laws to stamp out books in a very Moral Majority-era, Pro Christianity way. This downgrades my priors on coalition building always being a good thing. It also upgrades my prior on classical liberalism being the proper solution; ie all banning is bad. This is also an opportunity for an anti-illiberalism coalition to stand up, as evidenced by this op-ed by Kmele Foster (libertarian), David French (conservative), Jason Stanley (progressive), and Thomas Chatterton Williams (center left).

I still believe in coalition building. It's just a reminder to me to be aware of the motivations of the people you partner with. Moderates like me want everyone to have access to healthcare and a higher minimum wage. But I don't want to partner with the DSA because I worry they will use their power to destroy private businesses. Likewise, I wouldn't partner with an anti-woke organization if they are comfortable using illiberalism to get their way.

I've become obsessed w/a new investing thesis: products that let people exit or circumvent broken systems. A key freedom -- especially these days.

— Leo Polovets (@lpolovets) November 24, 2021

Examples:

fiat -> #Bitcoin

college degrees -> Lambda School

credit scores -> @wetradeup, @nova_credit

weak K-12 schools -> @Primer

This tweet reminds me of my credential free capitalism post, particularly the part about credit scores. I also need to do a deeper dive into this study on cash flow data, which is supposed to do a better job of predicting default than credit scores. I think its better for people on the margins to pursue new systems that allow them to circumvent traditional systems, rather than to force them into those traditional systems.

On the Jordan Peterson podcast, Jonathan Haidt said he was speaking to someone who said the authoritarianism aspect of Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory should actually be called something like "protectionism." It wasn't that conservatives necessarily like authoritarianism, just that they are comfortable invoking it when they feel protection is necessary.

This makes more sense and fits in with my dam metaphor. Instead of labeling things as right authoritarianism or left authoritarianism, it's better to think of things as "situations in which this group finds authoritarianism acceptable."

So tired of hearing people say "divisive." Utterly useless term.

— RIP CHARLES MILLS 🐐 (@deonteleologist) November 11, 2021

I don't care much for the above tweeter, but I think this post explains something I write about a lot. I think "divisive" is a very important term, but that's because I am an Enlightenment liberal, so I see tribalism as humanity's default setting and liberalism as the dam holding back the flood of civil war. This guy is a progressive, so he doesn't give a shit about civility or actions that turn up the tribalism dial. He sees the world through an oppressor vs. oppressed lens, and "divisiveness" is no reason to stop fighting the oppressors or advocating for the oppressed.

I am totally comfortable acknowledging my bias and that it's not necessarily "better" than anyone else's bias. The thing that chaps my ass is when members of the credential class fail to recognize their own bias and conflate it with truth. To them, it's not a moral disagreement. It's: "I'm smarter than you. I have the facts. You are wrong."

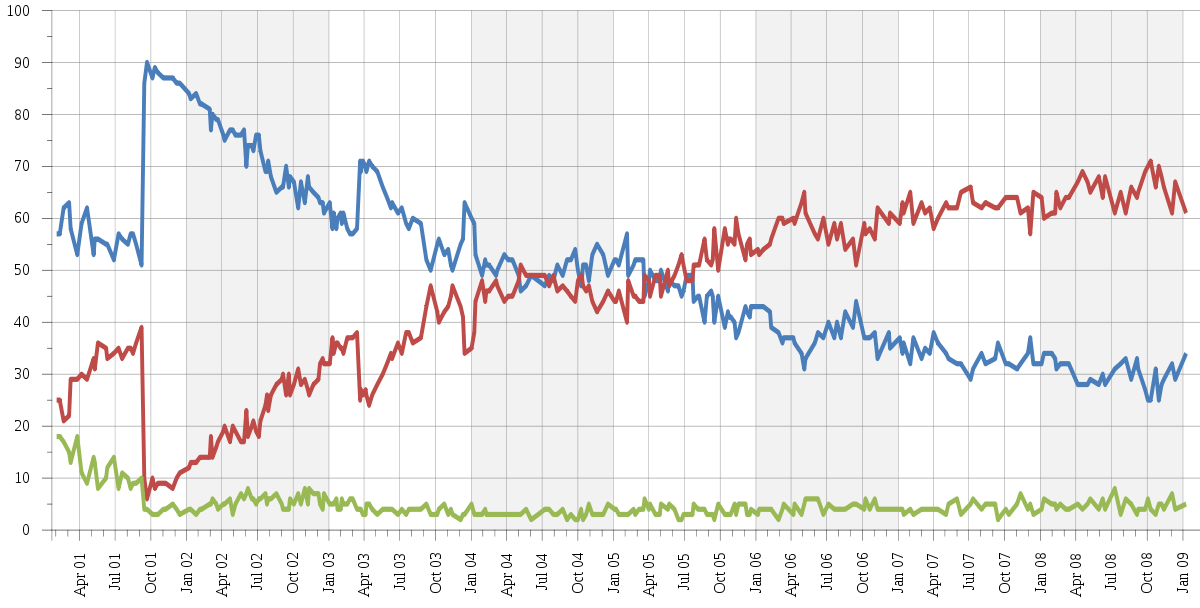

The drastic increases recorded in this poll are mind-blowing and provide strong empirical support for the claim that as oppression recedes, sensitivity to injury and indignity actually increases https://t.co/DgF43c0OpU pic.twitter.com/fUnJYIVVrZ

— Wesley Yang (@wesyang) November 11, 2021

Now we're entering the Confirmation Bias portion of Short Takes. This poll above made me think of my post about purple dots. If the lens you view the world is to look for oppression, you will fail to notice progress and broaden your definition of oppression.

If I'm an editor at Scientific American, one of a small subset of mainstream publications devoted solely to, well, science, I definitely want to jump in with an aggressive take on each and every culture-war controversy. Very very good for the brand.https://t.co/CZAF4I6AbR

— Jesse Singal (@jessesingal) November 10, 2021

This thread made me think of my post about bottomfeeders. I wrote "Let's say CNN had a 60% liberal bias in 1996, and that meant that of the stories they did not report, 80% of the time it was false and the other 20% was because it had a conservative angle they did not consider because they were too orthodox."

But I never gave a good example of the bolded section. The Scientific American is what I mean. If you read the full thread, Singal notes the authors makes it sound like this ant-CRT bill will ban all these books. Singal points out that a link in the story "points not to the bill itself, but to testimony from a state rep who argues the terms in question *potentially* violate the bill." In fact, the bill is publicly available for anyone to read. The journalists and editor just didn't bother to do so.

Other than laziness or intentional disinformation, I think the more likely story is a liberal bias that confirmed their priors. They didn't feel a need to follow up. A more conservative staff member would have smelled bullshit and searched for a reason to confirm his prior that this wasn't true, and probably found it. This is the value of intellectual diversity.