The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Friday, March 27, 2020

UBI(A): Universal Broadband Internet Access

One thing made clear from all this homeschooling is the need for internet access. On an Econtalk episode with Tyler Cowen, he and Russ Roberts discuss how social distancing might change society. We might find it more efficient to continue to work and learn remotely. If this trend continues, that means that guaranteeing public education for all children would have to guarantee internet access.

According to the FCC, 6 percent of US households do not have broadband access. That seems small (this says says 60 million, which would be 18 percent), but I can already give anecdotal stories from my father who teaches a community college course to working adults who never completed high school. One of his students has to go to McDonald's to send email. Now that restaurants are closed, I don't know what he's doing.

So why not subsidize?

This article in Reason shows that Lifeline, a federal program that subsidizes telephone and broadband internet service for low-income Americans, has been handing out subsidies to dead people. So efficiency and accountability might be an issue. One critique of Lifeline is that it offers the choice of a smartphone (remember Obama phones?) or internet access and most people choose the former. It's a harder sell to tell people that cell phones are a human right.

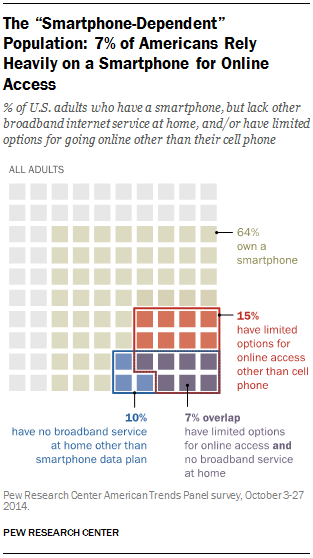

So is internet access even a problem? Here's some good news: Pew shows that internet usage is up dramatically. Even 66 percent of citizens without a high school diploma are on the internet. However, many of them are dependent on their smartphone for access, which isn't conducive to things like online learning.

This report shows that "19% of Americans rely to some degree on a smartphone for accessing online services and information and for staying connected to the world around them — either because they lack broadband at home, or because they have few options for online access other than their cell phone." (this might be where that earlier link gets their 18 percent number from.)

So even if we hand out Chromebooks to every student in America, an unacceptable number of them (roughly one out of five) won't be able to log into their teacher's learning portal.

It isn't just about affordability. Many rural communities don't even have the option to purchase broadband. It's often too expensive, meaning too little ROI, for private companies to build in rural areas. They get more money by setting up shop in denser, wealthier neighborhoods and profiting off that sweet monopoly money.

A growing trend is local communities building their own Internet networks. This interactive map shows you where.

Reason looked at a University of Pennsylvania study which examined 20 city-owned broadband networks around the country whose profitability could be gauged, 11 of which are operating at a loss.

They also link to an interactive map of 200 municipal networks showing that 14 have failed while another 50 remain mired in over $1 million in debt. In total that's 64 out of 200, so ... most of them work just fine?

I get it, libertarian-leaning Reason, there will be efficiency problems if we choose government over private business. But the status quo is leaving a lot of people out in the (virtual) cold and, if you believe in meritocracy, these people should be given a chance to prove their worth. Especially when the market is not providing them with that chance.

Instead of framing broadband internet access as an argument about it being a right vs. a luxury, it should be viewed as an extension of education, pre market and post market (an idea explained in my review of The Third Pillar).

Better yet, it should be thought of as an investment in human capital. We should make it easy for people to apply for jobs online, take online courses, become auto didacts via edX, or, hell, even Wikipedia.

We guarantee everyone a basic education, which doesn't seem to be doing much these days. At the very least we should guarantee them the chance to compete with an increasingly online world.

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

I was wrong about Trump

I've written many regretful blog posts here. Sometimes I write things that I disagree with after the fact. Sometimes I make forecasts that are proven wrong, such as my hopeful post about Trump from 2016.

I wrote:

In my post, I pulled this quote from FiveThirtyEight:

I also delivered this gem:

I wrote:

"Because now that he's president, America is his brand. He cares a great deal what other people think of him (almost to a fault ... no, definitely to a fault) and will want to make decisions based on how the country will look, not just himself."What I didn't predict was how much he would hitch his wagon to the stock market. Now we find ourselves in a predicament where he has to choose between supporting the stock market (ending social distancing and reopening businesses) and doing the right thing (continuing social distancing and saving as many lives as possible). He appears to be favoring the former.

In my post, I pulled this quote from FiveThirtyEight:

"Many of Trump’s major economic promises, however, would require cooperation with Congress and/or the Supreme Court. So repealing Obamacare, cutting taxes and building his infamous wall on the Mexican border — Trump couldn’t do that unilaterally."I didn't foresee how much the GOP would fall in line for fear of Trump turning his base against them. Like Trump, when the GOP also chose selfishly when having to choose between upholding conservative principles (free market, free trade, not putting kids in cages) and compromising those principles to stay in power.

I also delivered this gem:

"Now that Trump is president, if rejecting open trade and closing our borders to immigrants is as disastrous as most economists agree it will be, that gives voters empirical evidence that these ideas do not work for the next election."His policies have not done much to derail the economy. It's hummed along despite his interference. You can point out specific instances that have been negative, but in the aggregate employment and production have been just fine.

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

An update on my Sacrifices post

There are a few obvious reasons people are ignoring social distancing protocol and I didn't want to make it seem that "a lack of opportunities for heroism" is the best I could come up with.

First, it's easy to forget that many people aren't following the news as much as I am. It is quite likely that the young people on spring break read that they are at low risk for dying from infection ... and simply stopped reading after that.

They probably never considered the fact that they could be asymptomatic and pass the virus on to someone who could die from it. So simple ignorance is a very probable explanation.

Second, the parents in my generation might not be considering the fact that staying home is a bigger sacrifice for young people than it is for us. Now that schools have closed, my kids are already at home. I've been told to telecommute to work. So my biggest responsibilities, work and parenthood, have made the decision to quarantine for me.

For young people, for whom socialization is a big part of their life, staying under quarantine is a big sacrifice. Most college students don't work and are childless. I think it's easy to forget about this.

Finally, this is something I read years ago that I'm going to try to explain but I'll probably get something wrong. In a nutshell: The secondary effects of passing the virus on don't feel as real to us.

In Moral Tribes, Joshua Greene uses the philosophical trolley problem to explain how the mind works.

Greene found that the results changed a bit from the original scenario, with more people willing to be okay with the physical act of commission that leads to a bystander's death once the secondary track is added.

It seems that adding these secondary effects made the deaths less real to some people. Likewise, the idea of catching a virus and unknowingly passing it on to someone who dies from it, someone you never know, feels less urgent.

It's not lost on me that, in the trolley scenario, you get to save five lives; an act of heroism.

First, it's easy to forget that many people aren't following the news as much as I am. It is quite likely that the young people on spring break read that they are at low risk for dying from infection ... and simply stopped reading after that.

They probably never considered the fact that they could be asymptomatic and pass the virus on to someone who could die from it. So simple ignorance is a very probable explanation.

Second, the parents in my generation might not be considering the fact that staying home is a bigger sacrifice for young people than it is for us. Now that schools have closed, my kids are already at home. I've been told to telecommute to work. So my biggest responsibilities, work and parenthood, have made the decision to quarantine for me.

For young people, for whom socialization is a big part of their life, staying under quarantine is a big sacrifice. Most college students don't work and are childless. I think it's easy to forget about this.

Finally, this is something I read years ago that I'm going to try to explain but I'll probably get something wrong. In a nutshell: The secondary effects of passing the virus on don't feel as real to us.

In Moral Tribes, Joshua Greene uses the philosophical trolley problem to explain how the mind works.

"A runaway trolley is about to run over and kill five people. In the switch dilemma one can save them by hitting a switch that will divert the trolley onto a side-track, where it will kill only one person. In the footbridge dilemma one can save them by pushing someone off a footbridge and into the trolley’s path, killing him, but stopping the trolley. Most people approve of the five-for-one tradeoff in the switch dilemma, but not in the footbridge dilemma."Greene found that subjects' responses changed when they added in the loop variant as well as the obstacle/push collide variant.

"As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people and you can divert it onto a secondary track. However, in this variant the secondary track later rejoins the main track, so diverting the trolley still leaves it on a track which leads to the five people. But, the person on the secondary track is a fat person who, when he is killed by the trolley, will stop it from continuing on to the five people.

The only physical difference here is the addition of an extra piece of track."Here is a figure that may help.

Greene found that the results changed a bit from the original scenario, with more people willing to be okay with the physical act of commission that leads to a bystander's death once the secondary track is added.

It seems that adding these secondary effects made the deaths less real to some people. Likewise, the idea of catching a virus and unknowingly passing it on to someone who dies from it, someone you never know, feels less urgent.

It's not lost on me that, in the trolley scenario, you get to save five lives; an act of heroism.

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Sufficiently-Demanding Sacrifices

The above tweet from Elizabeth Bruenig is her take on the film Joker. I think her line about "a lack of opportunities for heroism" best gets at what the film and its cultural impact are about.

I haven't thought about that tweet until recently when I began to see content on Twitter responding to coronavirus like this:

There are numerous other instances of people heading out to bars and other crowded spaces, very much in spite of CDC recommendations, which has sparked responses like this:

I know there is less patriotism and civic trust now than in the 1940s but I can't help but think that the difference in the public response between WWII and coronavirus has something to do with what we are asking people to sacrifice.

I read somewhere that the religion with the most loyal followers will be the one that demands the most from its adherents. It should not be a surprise that suicide bombers abstain from alcohol and cover their women head to toe.

The people heading out to bars are people who are probably not going to die from COVID-19. We're not asking them to save their own lives, we're asking them to make a sacrifice for others. Is the problem that the sacrifice is demanding too little? After all, there is nothing heroic about staying home and watching Netflix.

Is the problem that the risk of exposure is actually enticing to these young men, since most of us have never had a rite of passage to prove our manhood?

Instead of paternalistic lecturing, I wonder if more people would listen if this was framed as an opportunity for heroism.

We need healthy young men to deliver groceries to the elderly, the immunocompromised, and those at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 who cannot leave their homes. We need adults without children to volunteer to watch the kids of doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals so they can go to work and keep our hospitals operating at maximum capacity.

We need you to be leaders in our communities because no one else is going to do it. We need heroes because the stakes are so high.

There are certainly people who are going to do what they want, no matter how you frame the conversation. Just as I'm sure there were students who did not want to give up their class ring during WWII. But there might be enough people willing to listen to make a difference.

I haven't thought about that tweet until recently when I began to see content on Twitter responding to coronavirus like this:

Downtown Nashville is undefeated. pic.twitter.com/BFIOzukFct— Janna Abraham (@SportsPundette) March 15, 2020

There are numerous other instances of people heading out to bars and other crowded spaces, very much in spite of CDC recommendations, which has sparked responses like this:

I remember talking to a nun at a college where I used to work. She was a student there during WWII. She talked about how they gave up their class rings because the country needed the metal for the war efforts. She described it as a sacrifice people were happy to make.Greatest Generation: Came together and laid down their lives to defeat Hitler in WWII.— Sean Kent (@seankent) March 15, 2020

Current Genrations: Hoarding toilet paper and refusing to stay home and watch Netflix so people don’t die.

I know there is less patriotism and civic trust now than in the 1940s but I can't help but think that the difference in the public response between WWII and coronavirus has something to do with what we are asking people to sacrifice.

I read somewhere that the religion with the most loyal followers will be the one that demands the most from its adherents. It should not be a surprise that suicide bombers abstain from alcohol and cover their women head to toe.

The people heading out to bars are people who are probably not going to die from COVID-19. We're not asking them to save their own lives, we're asking them to make a sacrifice for others. Is the problem that the sacrifice is demanding too little? After all, there is nothing heroic about staying home and watching Netflix.

Is the problem that the risk of exposure is actually enticing to these young men, since most of us have never had a rite of passage to prove our manhood?

Instead of paternalistic lecturing, I wonder if more people would listen if this was framed as an opportunity for heroism.

We need healthy young men to deliver groceries to the elderly, the immunocompromised, and those at highest risk of dying from COVID-19 who cannot leave their homes. We need adults without children to volunteer to watch the kids of doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals so they can go to work and keep our hospitals operating at maximum capacity.

We need you to be leaders in our communities because no one else is going to do it. We need heroes because the stakes are so high.

There are certainly people who are going to do what they want, no matter how you frame the conversation. Just as I'm sure there were students who did not want to give up their class ring during WWII. But there might be enough people willing to listen to make a difference.

Monday, March 16, 2020

When to Worry

Here is something I get stuck on. Letgrow.org has a mission of promoting free play among youth. They rally against the stigma that children are in constant danger, citing statistics that show how rare child abduction is. I believe in this.

I also believe in the Black Swanism of Nassim Taleb. The abduction of my children, however low a probability, is a tail risk: unlikely but incredibly damaging. So am I right to panic and over-prepare for such a scenario?

I guess the answer is: it depends. One of the most interesting reads I've come across is titled "Is Sunscreen the New Margarine?" The article posits that using sunscreen to prevent skin cancer is an overreaction that blocks vitamin D, thus increasing the risk of heart disease. The author believes that this trade off is actually worse.

This is like the study showing that any safety that comes with the protection of an oversized SUV is wiped out by its likelihood of rolling over.

I guess the answer to my dilemma is that it is okay to panic in preparation of a tail risk as long as the panic does not lead to an externality that is worse than the original thing I'm worried about.

For corona virus panic, social distancing, hand washing, and sanitizing have no major externalities and make sense no matter how small the risk of contracting illness. (I'm willing to admit that long-term isolation from quarantining can have damaging psychological effects.)

However, stocking up on masks and checking into the hospital after every cough are examples of panic that harm the supply of resources for people who really need it. This is an externality that overwhelms hospitals beyond capacity and actually makes things worse.

So there is good panic and bad panic; "better safe than sorry" panic with little trade off, and panic that leads to outcomes worse than if you had just done nothing.

Getting back to my original dilemma: I don't have a good way of measuring the trade offs between abduction prevention and cultivating mentally healthy children. Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have a lot of good research into the increase in anxiety, depression, and suicide attempts that correlate, somewhat, with helicopter parenting.

But I still don't feel confident about taking a side. Obviously if you gave me the option of my children being abducted or them having depression and suicidal ideations, I would take the latter. The damage is easy to compare between the two scenarios, but not the level of risk.

Kids being deprived social skills and the natural learning that comes from unsupervised and unstructured play seems pretty likely to increase mental health issues in their future. But lax supervision is still unlikely to lead to abduction, which is rare no matter what you do.

But it's not an apples to apples comparison. My children can only be abducted if I'm not around, so it's something I have a lot of control over. But there are so many factors that go into mental health, an area we don't totally understand to begin with. Giving my son a little more freedom might nudge him in a healthier direction but it still might not be enough to prevent his depression when so many other factors are brought in.

I started writing this blog post with the hope that I would find a rational solution but I'm still unsatisfied. All I can do is manage my panic as appropriate and be mindful that my actions aren't actually making things worse.

Wednesday, February 12, 2020

Review: The Third Pillar

The Third Pillar by Raghuram Rajan was a good read. Some of it was boring to me, some was really interesting and relevant, and some was interesting and irrelevant.

His basic argument is that societies are healthiest when there is a balance among the state, the market, and the community. He says the latter is what is lacking right now.

The most fascinating section was when Rajan commented on our abandoned inner cities from white flight and the decaying rural communities affected by globalization and automation. How do we address this problem knowing there is so much wealth, productivity, and human capital in many of our largest cities?

The liberal solution is to employ equity; tax the rich and use that money to make poverty tolerable. For the conservatives that care about poor people, their solution is to build meritocratic bridges and ladders for the poor to escape those communities and thrive in more productive and prosperous cities.

Rajan suggests a different idea: build bridges (slides?) that incentivizes the well-off to move into struggling communities and schools. This is equity without the coercion.

He cites a article from The Economist that notes:

Could some sort of bizzaro affordable housing zoning work? A poor community zones a neighborhood for new development that is 150 percent market rate? Anyone who moves in gets the same tax and college incentives he suggests?

Here are the other sections from the book I highlighted:

On Post-market support

On Rent Seeking

On Localism and Housing

On Social Capital

His basic argument is that societies are healthiest when there is a balance among the state, the market, and the community. He says the latter is what is lacking right now.

The most fascinating section was when Rajan commented on our abandoned inner cities from white flight and the decaying rural communities affected by globalization and automation. How do we address this problem knowing there is so much wealth, productivity, and human capital in many of our largest cities?

The liberal solution is to employ equity; tax the rich and use that money to make poverty tolerable. For the conservatives that care about poor people, their solution is to build meritocratic bridges and ladders for the poor to escape those communities and thrive in more productive and prosperous cities.

Rajan suggests a different idea: build bridges (slides?) that incentivizes the well-off to move into struggling communities and schools. This is equity without the coercion.

He cites a article from The Economist that notes:

“A study by researchers at Bristol University in 2006 found that the boost to a pupil attending a grammar school was worth four grades at GCSE, the exams taken at 16. But this comes at a cost. Those who fail to get into grammar school do one grade worse than they would if the grammars did not exist. The likely explanation is that grammar schools attract the best teachers, says Rebecca Allen of Education Datalab, a research group. There is no overall improvement in results as the benefit to the brightest is cancelled out by the drag on the rest.”In other words, students in poor performing schools benefit by being in a class with smart kids. Take the smartest kids out of theses schools and everyone is worse off (If true, this makes gifted tracking programs look pretty bad.) Here is Rajan on what his idea might look like:

“Another way of encouraging mixing, or at least discouraging sorting, is through tax code. High income households whose children are enrolled in public schools in low income districts could be given a tax rebate, essentially because of the positive spillovers that their children are likely to contribute to their class. Top universities could give incentives to students studying in public schools in low income districts by allocating a fraction of admits to each public school in the state… the presence of these well prepared children and their pushy highly educated parents in the schools will be beneficial to all.”I'm really intrigued by this, but it would have to be a pretty big incentive to get an upperclass suburban family to send their kid to the inner city. All it takes is one day of bullying for the parents to pull their kid.

Could some sort of bizzaro affordable housing zoning work? A poor community zones a neighborhood for new development that is 150 percent market rate? Anyone who moves in gets the same tax and college incentives he suggests?

Here are the other sections from the book I highlighted:

On Post-market support

“...pre-market support—help in preparing the individual to enter the market ... Post-market support—help to those who are hit by adverse economic conditions, or who, because of disability, misfortune, aging, or technological change, are incapable of earning a living ... today the U.S. schooling system is no longer adequate, hence more weight falls on post-market support, which the U.S. is ill structured to provide.”If pre-market support (our public school system) is not adequately preparing kids for getting jobs, maybe the solution is to spend less money there and more on post-market support.

On Rent Seeking

“As Adam Smith recognized, regulatory bodies often become subservient to the powerful among the regulated--in which case, paradoxically, regulations become a tool with which to protect the powerful and stifle competition.”Yes, you need the state to regulate business. But two things happen when the state gets too big. First, less is asked of the community to provide aid to their neighbors and people become less engaged civically and more individualistic (see the next quote below). Second, when the state gets too big it becomes prone to corruption. Big businesses will use it to snuff out competition, which ultimately hurts the consumer.

On Localism and Housing

“Progressives wanted freedoms that were tempered by responsibility toward the family and the broader community. In the short run, they pushed for greater government involvement. Unfortunately federal and state governments, as well as professional organizations like teacher’s associations, assumed greater power. This had the tendency to usurp communities, reducing local control as well as the customization of policies to local needs, leaving citizens less engaged.”

“... when inclusiveness goes up against localism, inclusiveness should always triumph … when we have to choose between competition and property rights, we should invariably choose competition.”I'm always a fan of, when introducing a new idea, someone points out the limitations and exceptions, which Rajan does well above when describing localism. More on housing:

[For example:] “A bill … would allow all housing being built within a half mile of a train station or bus route to be exempt from regulations regarding the height of the building, number of apartments, provision of parking spaces, or design specifics.”

“The state could mandate that some fraction of the residences in any community, say 15 percent, be affordable for low income residents. If the community would like to maintain its aesthetic look and allow only large single family residences, then a sufficient number of these should be rented or sold to low income families, with the rest of the community bearing the cost of making these affordable.”

“Countries that have a severe sorting problem could build in stronger tax incentives to mix, including residential congestion taxes that require rich households to pay higher taxes if they stay in communities with other rich households, and lower taxes if they stay in low income communities.”Massachusetts has tried to do this with smart growth zoning. This is a tough issue because it requires local government to solve a national problem (affordable housing), when local government does not benefit from it. It feels like a Nash equilibrium problem where we need the state to step in to coordinate efforts. No community wants low income housing since they worry it will lower property values. If each community allowed it, it would be fine. But the first community to allow low income housing will be less desirable compared to all the other communities that have zoned it away, leaving no incentive for anyone to defect.

On Social Capital

“...Italian cities that achieved self governance in the Middle Ages have higher levels of social capital today—as measured by more non profit organizations per capita, the presence of an organ bank (indicating a willingness to donate) and fewer children caught cheating on national exams. Self governance instilled a culture that allowed citizens to be confident in their ability to do what was needed … decentralizing power to the communities may thus reduce apathy and force their members to assume responsibility for their destinies rather than blaming a distant elitist administration.”Finally, I was intrigued by his mention of the Elberfield System. From Wikipedia:

"The administration of poor relief was decentralized. Working under a citywide poor office, sub departments were established in smaller precincts—their relief workers worked on behalf of the central office.Unfortunately, attempts to introduce the system in non-German cities were unsuccessful.

Each precinct was in the care of an nonsalaried almoner whose duty was to investigate each applicant for aid and to make visits every two weeks as long as aid was given.

Key to the system was that the almoners and overseers served voluntarily. They came mostly from the middle class, being minor officials, craftsmen or merchants. Women were also accepted as almoners, giving them a rare (for the time) opportunity to participate in public life. The larger number of volunteers decreased both the number of clients per almoner, and the total system costs.

The system gave great satisfaction; the expenses in proportion to the population gradually decreased, and the condition of the poor is said to have improved."

Sunday, February 9, 2020

Status Quo Voting

I've written too many words about the lack of civic engagement and how I wish it would reverse course; there are too many extremists involved in all levels of politics and civic organizations.

But I have a new theory to explain the decline: most people do not want to vote. They just want to live their lives and not be bothered. The only thing that can motivate them to change their plans—so that they drive to their local voting location and cast their ballot—is the fear that if they don't, something will fundamentally alter their lives. Let's call it status quo voting.

- The Lewinsky scandal and Gore's stiff, elitism turned many non voters into status quo voters who just wanted a regular guy who would have a beer with them.

- When Regular Guy George W. Bush started an unpopular war, became a polarizing figure, fought against growing-in-popularity marriage equality, and his regularness started coming off as dumb, newly-formed status quo voters supported Obama. They wanted an intellectual, a uniter, someone dovish and progressive.

(I have trouble explaining what happened next but I'll do my best.) - Many non partisan doves disliked Obama's foreign policy, and believed Trump's nationalism would be less likely to engage in future wars. That was part of the Trump coalition. Many thought Clinton was too elitist/woke and continued to ignore the effects of automation. A lot of people just didn't like the Clinton brand and voted against it.

- There were also probably a good number of non voters for whom status quo means fewer immigrants, no more "press 1 for English", and a return to calling the town's "Holiday Tree" the "Christmas Tree". Status quo means the 1950s and Trump was the first candidate to promise such a thing. Yes, racism. I'm talking about racism.

The natural impulse of status quo voters is to vote for the candidate who most opposes the things they hate about the other party. But there is a better solution that doesn't come to us so intuitively.

Instead, status quo voters should vote for moderates in the party they hate. They will do a better job of watering down the extremism. Voting for extremists to fight the party you hate will only motivate other status quo voters to support extremists that fight back. Scott Alexander found this phenomenon while researching the effects of extremist candidates on voter turnout.

This goes back to my equilibrium problem. Things are better when there is equilibrium within institutions as opposed to among institutions.

So if you don't vote but you hate the AOC-style woke brigade, don't turnout for someone like Ted Cruz, vote for someone like Katie Hill, Abigail Spanberger, or any of the new moderate Democrats who "are less interested in a 70 percent top tax rate or a Green New Deal than they are in passing targeted fixes to protect the Affordable Care Act and lower the cost of health care, promoting renewable energy, and maybe looking for an infrastructure deal to fix crumbling roads and boost rural broadband to speed up slow internet in their districts."

If you don't vote but you hate Trumpian nationalism, Randian libertarianism, or McConnell's stubbornness, don't vote for the Squad, vote for someone like Suzanne Collins, Mitt Romney, Ben Sasse, or some new Republican challenger in the same vein.

You're more likely to find something resembling the status quo by moderating the thing you hate than emboldening somebody to fight it. Otherwise you get stuck in a ping pong match of over corrections.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)