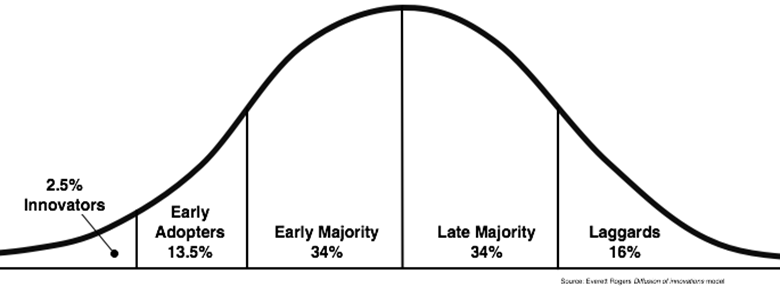

There is a theory called the diffusion of innovation that looks at how to capture market share. A certain group of the public (innovators, early adopters) will be the first in line to get the first-ever iPhones. The last group, the laggards, won't give up their flip phone until Samsung stops making it.

Most others are somewhere in between. Maybe it's like Mark Granovetter's concept of the riot rock threshold.

"In his view, a riot was not a collection of individuals, each of whom arrived independently at the decision to break windows. A riot was a social process, in which people did things in reaction to and in combination with those around them. Social processes are driven by our thresholds—which he defined as the number of people who need to be doing some activity before we agree to join them."

So the first person to throw a rock has a threshold of zero. The second person has a threshold of one, he never would have thrown the rock until someone else did. On and on until you get to the hundredth person who never would have joined the riot if 99 people before didn't step in.

I think this model is helpful for understanding rhetoric. If there is a cause you care about, your message should depend on whom you are speaking to.

Activists, Unengaged, Stubborns, and Persuadeables

Say your cause is climate change. The early adopters are the Greta Thunberg's of the world, the people who care as much as you. Let's call them The Activists. You don't need to convince them of the severity of climate change, you just need to give them direction on how to mobilize and take action.

The second group is The Unengaged. They don't have a stance and don't really care. Your message needs to be one of education. If they understood more, some will care as much as you and will join your cause. (In the case of vaccinations, this is the group that isn't motivated to get a free life-saving vaccine until you entice them with a $1 million vaccine lottery.)

The third group opposes you. Maybe they think climate change is a hoax. Maybe they think the threat is overblown. Maybe they just oppose anything progressives support.

This group has two subgroups; those open to changing their mind and those who are not. For the latter, don't even bother. In fact, the best you can do is not piss them off so they turn into activists who oppose your cause and make life harder. For the other sub-group, your message is one of persuasion. You have to know their beliefs and have good counterpoints. Let's call these subgroups The Stubborns and The Persuadeables.

Winning Converts

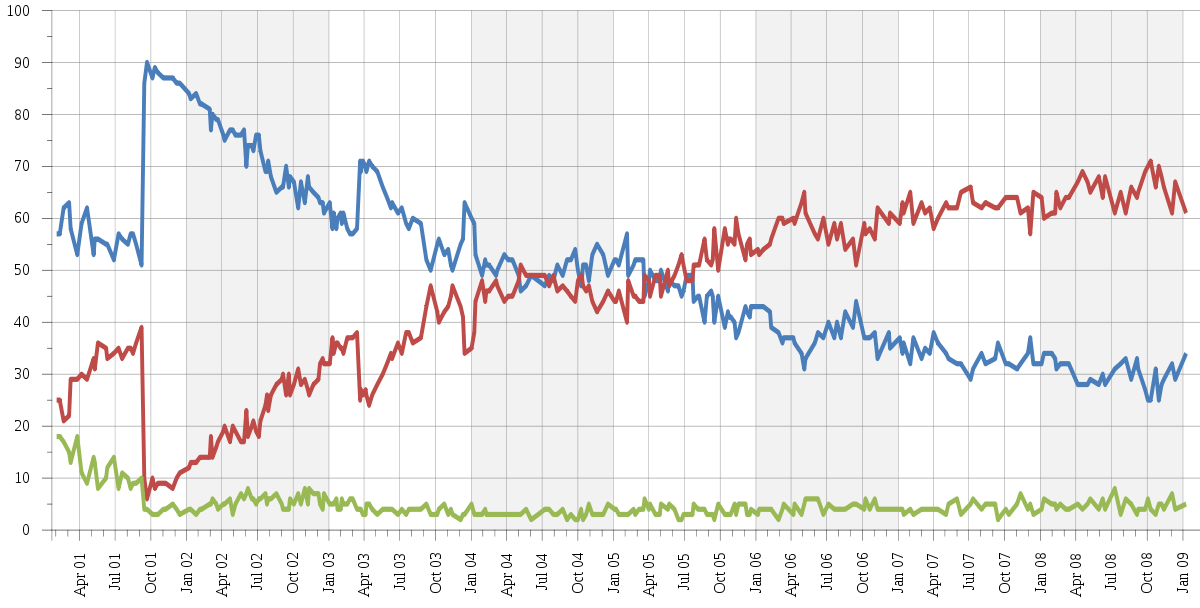

If these groups are anything like the rioters, the most efficient method will probably be to target the second group, The Unengaged. Not only are they the largest, but they likely have a domino effect. Once one of them becomes joins your cause, a second person, with a conversion threshold of one, will join him. Then another and another. As I noted in a previous post, the biggest change in support of Black Lives Matter came from people who had no opinion of the group (i.e. The Unengaged); there was little movement among people who opposed BLM.

But then again, it might make more sense to target The Persuadables. Jetty Taylor is a conservative who made frequent media appearances where he expressed his skepticism toward climate change. In The Scout Mindset, Julia Galef describes how climate activist Bob Litterman was able to persuade Jetty by speaking his language. Now, Taylor is an activist for environmental causes.

It might be easier to convince The Unengaged that you are right, but the most they will do is vote or donate in your direction. You cannot convince someone to become an activist, it's more of a personality type. That is why it might be more efficient to convert a Persuadable activist like Jetty, he will do more for your cause than 100 converted unengaged types.

The problem is targeting the message. If anyone outside The Activists hears an activist message, it will come across as preachy and condescending at best. At worst, it will mobilize The Stubborns to oppose you. Even a message for The Unengaged can sound preachy and condescending. For the uneducated on climate change, you need to create a simple story. The Stubborns and The Persuadables are often educated on the topic, or at least think they are, and will poke holes in your simple story and create their own narrative.

For The Persuadeables, you have to leave activism out of your message if you even want to engage. Then you have to know their side of the argument better than them. Then you have to deliver your message in a way that makes it easy for them to change their mind.

Controlling the Narrative

The other challenge is not letting The Activists take control of the narrative. They know the messaging that works for them, but they do not realize how ineffective it is against everyone else. They are unable to distinguish The Uneducated from The Stubborns so they think a simple message of education should work on everyone. They don't know how The Stubborns and Persuadables think.

Matt Yglesias wrote a great post called "Who is the racial justice case for zoning reform for?" He writes about zoning regulations and shows how they have empirically slowed economic growth, in addition to contributing to racial disparities.

If your focus on racial justice, you can motivate The Actvists. If you focus on economic growth, you can motivate The Persuadeables who support free markets. But if social justice activists hear the latter message, they might oppose you since the benefits of housing conflict with their anti-market beliefs.

"the people I am trying to convince are generally ideologically motivated college-educated professionals ... They conceive of urban land use politics as pitting activists or regulators against developers and are disinclined to side with the developers...

"The problem is that the very same racial angles that help zoning reformers win intra-progressive arguments have the opposite impact on the right... A struggle against white supremacy sounds a lot more righteous than a struggle against inefficient regulation."