I really enjoyed the Jonathan Rauch column I reviewed because it gave an answer to my favorite question: what caused the decades-long decline of social capital? All forms of civic engagement—working for a political party, going to church, volunteering for Kiwanis, even bowling—require trust in an institution, in some type of structure that asks for buy-in from its participants.

Even bowling in a league requires people to become a "member" of the league and follow its rules.

The Atlantic ran a story about how the end of the landline is affecting modern families. The more telling tale is the rise of viewing devices; each house having multiple flat screens, smartphones, tablets, and laptops for each family member to watch their own show.

TV monoculture is over because producers no longer have to create shows that appeal to everyone. Family viewing—itself an institution, featuring two dictators (the parents) determining what is best for the proletariat (the kids)—is a thing of the past. Each member has their own device and can watch their own type of show.

The atomization of the family unit is moving people toward more private and individual lives, and away from the structures that invite people into public life, or even the family room.

Helicopter Parenting

The authors of The Coddling of the American Mind, the author of iGen, and websites like Let Grow blame a lot of the problems with today's youth--like anxiety and depression--on helicopter parenting. They say it is important for kids to have unstructured unsupervised play and parents are not allowing that.

But what if it's not that simple? What if kids are leaving the house less because they don't want to, because they like the quality of entertainment at their disposal and don't feel compelled to leave the house to make new friends of have social interactions with current ones?

The average family is also smaller, so there is less experience with compromise. They don't have the necessary experience for negotiating public life and working through conflict.

Social Diabetes

Here's what I don't get: why does it feel good to do something that is bad for us?

Why does it feel better to read a book on philosophy in a quiet room than to attend weekly Mass?

Why do I enjoy sitting on my living room couch, scrolling through my Twitter timeline, putting a show for my son on our TV, and putting Netflix on our laptop for my daughter, as opposed to picking something we all can watch?

Why do I write blog posts about how disappointing I find our politicians to be instead of volunteering for the campaign of someone I believe can do better?

Eating I understand. Sugar is rare in the natural world, and our bodies need it in small amounts, so we have adapted traits that tell us to load up when something tastes sweet, knowing we might not find it again for weeks.

We understand that high levels of sugar are bad for us and are at least working on it. I feel like we understand the harmful effects of pulling away from public life, but we're not too concerned about it. There are public campaigns about opioid abuse and suicide, but not about their root causes: loneliness and isolation.

People choose personalization over sharing and compromise when given the choice. We choose to unite over a common enemy rather than work on a common project. The upshot is that this is terrible for society. It brings out the worst in our tribal impulses. We have no experience sharing in our personal life and expect democracy and society to be the same.

We're all coming up with Type II social diabetes but we're okay with the tradeoff because the saccharine personalization of entertainment tastes so damn good.

It could be that we've just never had the opportunity for personalization in human history, so we don't know how to deal with its externalities. But I'm growing less confident that we'll get to a point where we realize how bad this is for all of us and actually do something about it.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Start here: https://bayesianfox.blogspot.com/2010/12/genesis.html

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Best of 2019

Below are the best things I read or listened to in 2019.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Jonathan Rauch has two appearances. The guy has a knack for arguing for something I disagree with, but making so many good points that I have to take the argument seriously.

Two Ezra Klein podcasts make an appearance. If his episode with Jonathan Haidt had been a few weeks later, it would have made the 2019 cutoff and appeared as well. Even so, their conversation is the topic for a different story that made the list.

Jonathan Rauch

"In many respects, institutions are enemies of tribalism, at least in the context of a liberal society. By definition, they bring people together for joint effort on common projects, which builds community. They also socialize individuals and transmit knowledge and norms across generations. Because they are durable (or try to be), they tend to take a longer view and discourage behavior that considers only self-interest in the very short term...

"The more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."

Jonathan Rauch and Ray La Raja

"Turnout in primaries is notoriously paltry, and those who do show up are more partisan, more ideological, and more polarized than general-election voters or the general population. They are also wealthier, better educated, and older.”

"When party insiders evaluate candidates, they think about appealing to overworked laborers, harried parents, struggling students, less politicized moderates, and others who do not show up on primary day—but whose support the party will need to win the general election and then to govern. Reducing the influence of party professionals has, as Shafer and Wagner observe, amplified the voices of ideological activists at the expense of rank-and-file voters."

Ross Douthat

"[W]e should subdivide the “despair” problem into distinct categories: A drug crisis driven by the spread of heroin and fentanyl which requires a drug policy solution; a surge in suicides and depression and heavy drinking among middle-aged working-class whites to which economic policy might offer answers; and an increase in depression and suicide generally, and among young people especially, that has more mysterious causes (social media? secularization?) and might only yield to a psychological and spiritual response...

"But at the same time the simultaneity of the different self-destroying trends is a brute fact of American life. And that simultaneity does not feel like just a coincidence, just correlation without entanglement — especially when you include other indicators, collapsing birthrates and declining marriage rates and decaying social trust, that all suggest a society suffering a meaning deficit, a loss of purpose and optimism and direction, a gently dehumanizing drift."

Peter Beinart

“There is a secrecy “heuristic”—a mental shortcut that helps people make judgments. “People weigh secret information more heavily than public information when making decisions,” they wrote. A 2004 dissertation on jury behavior found a similar tendency. When judges told jurors to disregard certain information—once it was deemed secret—the jurors gave it more weight.

"While it’s unlikely Trump has heard of the secrecy heuristic, his comments about murder on Fifth Avenue suggest he grasps it instinctively. He recognizes that people accord less weight to information that nobody bothers to conceal. If shooting someone were that big a deal, the reasoning goes, Trump wouldn’t do it in full public view.

"By openly asking Ukraine and China to investigate a political rival, Trump expressed confidence that he’s doing nothing wrong. And while one might think the majority of Americans would view Trump’s confidence as an outrageous sham, academic evidence suggests that con men can be surprisingly difficult to unmask."This article is what made me think that Trump truly has something to hide in his tax returns. It's the only thing he keeps secret, which is probably why I give it more weight. But given what we know about Trump, it's probably less nefarious and more embarrassing. My guess is that he doesn't have as much money as he wants people to think.

"The Ideological Turing Test: How to Be Less Wrong"

Charles Chu

Charles Chu

"What we believe as ‘true’ today is just a small blade of grass in a miles-wide graveyard of ideas.

"Much of what we believe today is doomed to join other infamous dead theories like Lamarckism (“Giraffes have long necks because they used them a lot.”), bloodletting (“Let me put a leech on your forehead. It’ll cure your allergies. I promise.”), and phrenology (“I’m better than you because I have a bigger head.”)...

"Bryan Caplan says that I should understand my opponents’ ideas so well that they can’t tell the difference between what I am saying and what they believe."

A guide to the most—and least—politically open-minded counties in America"

Amanda Ripley, Rekha Tenjarla, Angla Y. He

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

This project, which measured the U.S. counties by political tolerance, sparked one of my own blog posts.

John Wood Jr.

"Klein worries that the solutions to the problems that concern Haidt and Lukianoff are also wicked in precisely the opposite direction. Civility and moderation, desirable qualities for political discourse and decision making, can numb us to the imperative of social change.

"Klein argues that successful activism has a history of making people uncomfortable, who would otherwise simply ignore injustice. 'Confrontation is unpopular, and often necessary, in part to get people to see things they don’t want to see.'

"We must realize that the maintenance of dignity in activism does not require the abandonment of fervor."This too sparked a blog post of mine.

Podcasts

The Rewatchables: The Shining featuring Bill Simmons, Sean Fennessey, and Chris Ryan

The Ezra Klein Show: Michael Lewis reads my mind

The Ezra Klein Show: Matt Yglesias and Jenny Schuetz solve the housing crisis

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

Slate Star Codex

Because my favorite blog deserves its own category

"NEW ATHEISM: THE GODLESSNESS THAT FAILED"

Scott notes the decline in new atheism, specifically in liberal circles. His answer: New Atheism was a failed hamartiology, a subfield of theology dealing with the study of sin, in particular, how sin enters the universe.

So how does that impact liberal circles?

"As it took its first baby steps, the Blue Tribe started asking itself “Who am I? What defines me?”, trying to figure out how it conceived of itself. New Atheism had an answer – “You are the people who aren’t blinded by fundamentalism” – and for a while the tribe toyed with accepting it. During the Bush administration, with all its struggles over Radical Islam and Intelligent Design and Faith-Based Charity, this seemed like it might be a reasonable answer. The atheist movement and the network of journalists/academics/pundits/operatives who made up the tribe’s core started drifting closer together.

Gradually the Blue Tribe got a little bit more self-awareness and realized this was not a great idea. Their coalition contained too many Catholic Latinos, too many Muslim Arabs, too many Baptist African-Americans. Remember that in 2008, “what if all the Hispanic people end up going Republican?” was considered a major and plausible concern. It became somewhat less amenable to New Atheism’s answer to its identity question – but absent a better one, the New Atheists continued to wield some social power.

Between 2008 and 2016, two things happened. First, Barack Obama replaced George W. Bush as president. Second, Ferguson. The Blue Tribe kept posing its same identity question: “Who am I? What defines me?”, and now Black Lives Matter gave them an answer they liked better “You are the people who aren’t blinded by sexism and racism.”"BOOK REVIEW: THE SECRET OF OUR SUCCESS"

"The author, Henrich, wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence." This made me think of a Nassim Taleb quote: not everything that happens, happens for a reason. But everything that survives, survives for a reason.

"Henrich discusses pregnancy taboos in Fiji; pregnant women are banned from eating sharks. Sure enough, these sharks contain chemicals that can cause birth defects. The women didn’t really know why they weren’t eating the sharks, but when anthropologists demanded a reason, they eventually decided it was because their babies would be born with shark skin rather than human skin."One of the reasons I like Scott is the he is critical of his own beliefs. This book is actually an argument against rationalism. The irrational idea that eating shark will give your baby shark skin is an idea that survived for so long that it must have a reason, however irrational it appears.

"WAGE STAGNATION: MUCH MORE THAN YOU WANTED TO KNOW"

Scott tackles the complexity of wage stagnation with all the nuance I've come to expect from him. A quick summation of his findings:

"If you were to put a gun to my head and force me to break down the importance of various factors in contributing to wage decoupling, it would look something like (warning: very low confidence!) this:Shameless Self-love

– Inflation miscalculations: 35%

– Wages vs. total compensation: 10%

– Increasing labor vs. capital inequality: 15%

—- (Because of automation: 7.5%)

—- (Because of policy: 7.5%)

– Increasing wage inequality: 40%

—- (Because of deunionization: 10%)

—- (Because of policies permitting high executive salaries: 20%)

—- (Because of globalization and automation: 10%)"

My favorite blog posts written by yours truly.

"Strong institutions or inclusive parties?"

Can colleges and universities become the new institutions that millenials trust or will we continue down the road of tribalism?

"Ideological Equity"

Weighing the best version of ideological equilibrium for powerful institutions. It's hard to summarize ...

"In Data We Trust"

How does trust in one state compare to another. How does trust in the U.S. compare to other countries? What causes, or at least correlates with, high levels of trust. Lots of graphics in this one.

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

A National Network of Community

One pattern Tyler Cowen observes in The Complacent Class is the growing reluctance of Americans to switch jobs and move to another state.

A common response is that poor people don't have the financial means to move, even if it means a better job. I'm not sure I entirely buy that. At the very least, it's only telling part of the story.

So what is keeping low-wage workers in low-productivity towns?

Personally, the number one reason I don't move is that my family is here and I don't like meeting new people. I have a very narrow window for people I'm not related to that I actually like spending time with. But if I knew MY TYPE OF PEOPLE would be in a new community where I have a job opportunity, I might consider moving.

That is why I wonder how much the decline of attendance in national institutions have had on geographic mobility. There has been a rise in independent protestant and Evangelical churches over the past 30 years and a commensurate decline in Catholic, Episcopal, Southern Baptist and United Methodist churches.

The advantage of having a national brand of religion is that you can be sure a community of like-minded believers will be waiting for you when you move to a new area. The same goes for Rotary International or any other civic organization.

When institutions are localized, it stymies the incentive to move somewhere different where you might not feel welcomed. Having a social infrastructure in place, where you already have some type of membership, at least gets you a foot in the door.

If family is what keeps me rooted, community is what can lure me away. A national network of ideologically-driven colleges and universities might be able to Make America Mobile Again.

This article traces it a little better and finds a similar conclusion.

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Strong institutions or inclusive parties?

I.

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

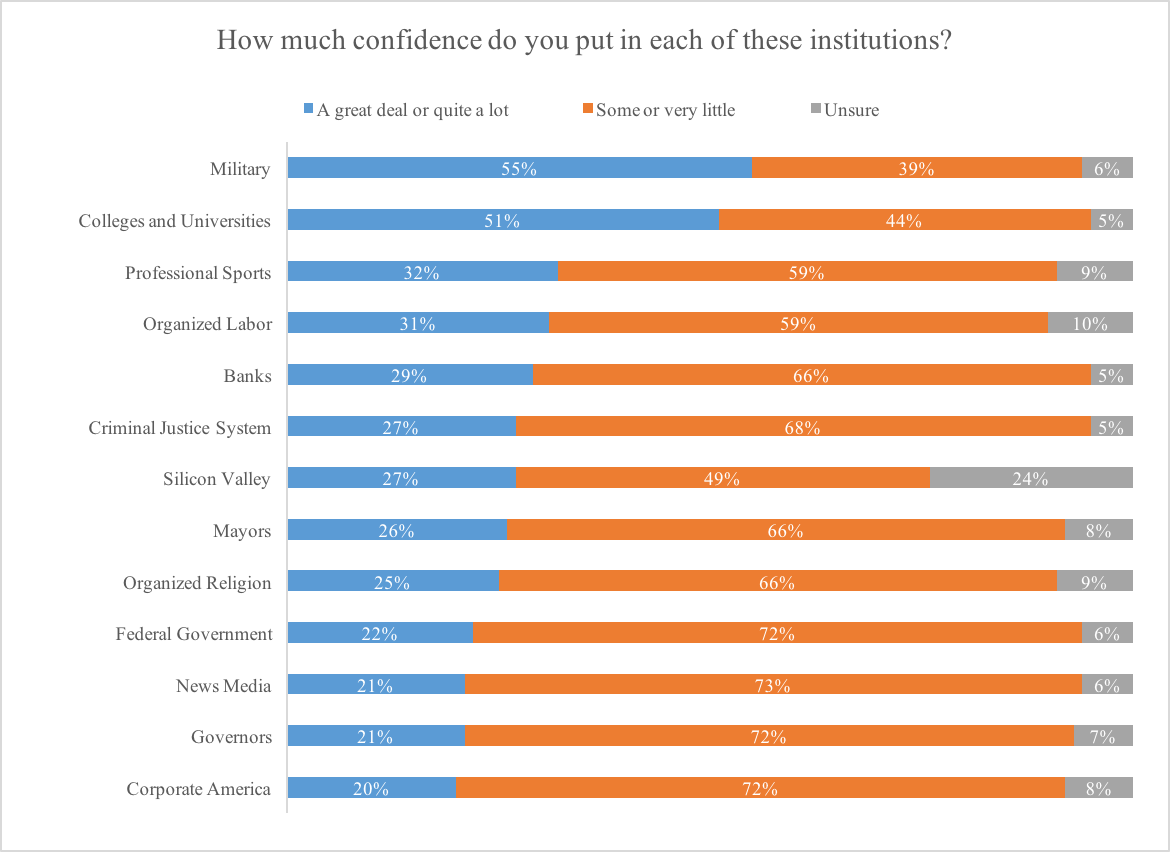

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

Jonathan Rauch wrote a wonderful article called "Rethinking Polarization" in which he ultimately concludes that strong institutions are the antidote to tribalism. And those institutions that we should think about rebuilding are the Democratic and Republican parties. I like his idea but I think it comes with a catch.

I've long hated the two party system. I often vote for a third party. But is it possible that—with the relative success of Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Andrew Yang—Democrats and Republicans can be enough?

Bernie is a socialist who happens to be in the Democrat party despite being far left of the average Democrat voter. Yang said he only chose to run as a Democrat because it was closest to his values and he does not identify strongly with the party. Trump, a former Democrat, is anathema to many (most?) Republican values. Even former Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul is more libertarian than Republican.

They all probably make more sense as third party candidates but they understand that they need to wear their respective D/R hats to get elected. Maybe my dream of stronger third parties (or even no parties) will never come to fruition, but two large heterogeneous parties is a pretty good consolation prize.

Maybe the best thing the success of Bernie and Trump ever did was to convince party outsiders that they can succeed even if they don't match the archetypal party member. Now, I don't like either of them and would prefer less extremism, but I do like Yang (I'd like him better if he held office first and ran again later) and I don't consider him extreme. I'd say the same about Ron Paul.

So while I don't like most of the aforementioned candidates, I like the fact that the parties are open enough for them to get national attention.

I also think I would like this path even better with ranked-choice voting. This would give party candidates more room to tout their beliefs without fear of having to play to a base that doesn't even represent most citizens. Open parties would also solve the equilibrium problem, balancing the extremes in each party with more moderates.

II.

Rauch traces the root of polarization to a movement in the 1950s to make the parties more distinct. I'm fine with them being distinct from one another, as long as they are diverse and inclusive within their own party. I don't know if it's enough to stop the rising tide of individualism, but it's worth trying.

Rauch also believes that stronger parties would have weeded out candidates like Sanders and Trump. So his vision of stronger parties might come at the cost of new ideas, pushing more people to run as hopeless third party candidates. That is why I think that the Democrat and Republican parties are not the answer, even if institutions are.

But there are still good ideas in his article. In fact, what really caught my attention was this section:

"Paradoxically, partisanship has never been stronger, but the party organizations have never been weaker — and this is not a paradox at all. When they had the capacity to do so, party organizations engaged citizens in volunteer work, local party clubs, and social events, giving ordinary people a sense of political engagement that merely voting or writing a check cannot provide. Until they lost the power to do so, they road-tested and vetted political candidates, screening out incompetents, sociopaths, and those with no interest in governing. When they could, they used incentives like jobs, money, and protection from primary challenges to get legislators to work together and accept tough compromises. Perversely, the weakening of parties as organizations has led individuals to coalesce instead around parties as brands, turning organizational politics into identity politics.

To put the point another way, the more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy."And later:

"Getting traction against affective polarization and tribalism will require some direct measures, such as civic bridge-building. Even more, it will require indirect measures, such as strengthening institutions like unions, civic clubs, political-party organizations, civics education, and others. Above all, it will require re-norming: rediscovering and recommitting to virtues like lawfulness and truthfulness and forbearance and compromise."I want to believe that strong parties can build social capital and strengthen communities. Can we have that without pushing outside candidates to the margins?

III.

Personally, I think the trend of abandoning of institutions is eventually going to fail and the next generation will have to build their own institutions to sustain a healthy society. My guess is that they will start fresh with new institutions.

Ultimately, I think we're going to be fine but it might look rough for a few years.

And yet ...

I'm still stuck on this idea: Can parties be distinct from one another and internally heterogeneous? This Slate Star Codex post traces how the left came to self-identify as "we're the party that isn't racist and sexist".

I guess the right has been "we're the party that fears God and loves freedom".

The problem with this approach as that the parties are identifying themselves by what they are not or by what is wrong with the other party; this is the result of the tribalism that Rauch describes. Democrats used to be about strengthening labor unions and lifting people out of poverty. Republicans used to be about growing business and encouraging responsibility.

In order for these institutions to be strong again, and to resist tribal impulses, they must define themselves by the good they do. But institutional decay might be reverse causality; the parties might be responding to the growing tribal/individualistic nature of society and they probably won't change until people do.

Partisanship will have to get really nasty before it turns people away and they seek the more positive message that institutions can supply. I've argued that groups like Better Angels are better off seeing themselves as a new institution rather than trying to rebuild the relationships between increasingly extreme Democrats and Republicans. Better to leave those extremists behind and build coalitions with normal Americans.

So while I agree with Rauch that strong institutions are a guard against tribalism, I disagree that the Democrat and Republican parties are the answer. We'll have to build something new.

IV.

So what do Millennials trust?

According to The Millennial Economy report, colleges and the military stand out at just over 50 percent. Maybe that is enough. Can those institutions replace liberal and conservatives groups?

This Harvard poll also found majority trust in scientists. Not really an institution, unless they're seen as an extension of colleges.

Somehow, I just don't see higher education and the military working with local communities and civic organizations. Especially colleges, which seem to be growing more tribal.

But, I've always liked Jon Haidt's idea of colleges being upfront about their telos: truth or social justice. Maybe these can be the new institutions to replace parties: two types of colleges that are distinct from one another and seen as trustworthy by citizens.

Noah Smith believes that small colleges can save rural American communities. Maybe this is the future?

What if we invest more in research universities in flyover country? Their telos can match the values of the community. People's loyalty to their local college or university will supersede their tribal nature. The university can take the lead in local, regional, or even national politics, leading and reflecting the values of their community.

They could endorse candidates and provide opportunities for civic engagement. Universities in urban progressive areas can serve social justice needs and reflect their constituents.

Conclusion

- Strong institutions might allay our country's current tribal crisis, but I'd really like to research this idea more.

- If the result of weakening political parties is that they make room for outside candidates who otherwise would have run as a third party, I think that is a good thing.

- I'm not convinced that we can revive the Democrat and Republican parties to their 1950s strength. We (meaning Millenials and Gen Z) might have to put our faith in new institutions.

- If colleges follow the Jon Haidt model and be transparent about their ideology, people will choose whichever matches their preference. Investment in more colleges, especially in this model, might lead to strong institutions that people trust, which will build loyalty to the institution that can then reduce tribalism.

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

What if they don't want your help?

I've always admired the progressives' work to advocate on behalf of the poor, downtrodden, marginalized groups of society. But lately I've begun to wonder if their efforts are in vain.

Are they too performative? Are they overapplying instances of oppression? Are they trying to fix a problem that isn't actually a problem?

Marriage

This Quillette story deals with how elites use coded language and espouse particular beliefs as ways of signaling their class status. Ultimately, I think the author engaged in bad-faith reasoning in an otherwise well-written and researched column. I happen to think progressives, for the most part, are doing what they think is in the best interest of the oppressed.

However, the author makes an interesting point, noting that:

"...in 1960 the percentage of American children living with both biological parents was identical for affluent and working-class families—95 percent. By 2005, 85 percent of affluent families were still intact, but for working-class families the figure had plummeted to 30 percent.

Upper-class people, particularly in the 1960s, championed sexual freedom. Loose sexual norms spread throughout the rest of society. The upper class, though, still have intact families. They experiment in college and then settle down later. The families of the lower class fell apart. Today, the affluent are among the most likely to display the luxury belief that sexual freedom is great, though they are the most likely to get married and least likely to get divorced."I don't know that I completely buy the notion that hippies are the cause of the dissolution of the working class family unit (but Mary Eberstadt thinks so), but those marriage rates by class are important figures.

I'd like to probe deeper into what kept poor families together prior to the 1960s? Was social norms and fewer working opportunities for women keeping them in bad marriages? Divorce tends to correlate with money problems; perhaps stronger unions and less inequality kept poor families together?

Microaggressions

I'm all for bringing as many people into the American fold as possible. If there is a way for minorities to feel more welcome at college, I'd like to hear more. But I suspect that many progressives are trying solve a problem on behalf of a group, when it's only a "problem" for a very small portion of said group.

There's the poll noting that only 2 percent of Latin Americans actually prefer the term "Latinx."

Writing in The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf notes that many colleges are using examples of phrases to avoid as they are "racial microaggressions." However, he cites a Cato/YouGov survey on free speech and tolerance that finds:

"Telling a recent immigrant, “you speak good English” was deemed “not offensive” by 77 percent of Latinos; saying “I don’t notice people’s race” was deemed “not offensive” by 71 percent of African Americans and 80 percent of Latinos; saying “America is a melting pot” was deemed not offensive by 77 percent of African Americans and 70 percent of Latinos; saying “America is the land of opportunity” was deemed “not offensive” by 93 percent of African Americans and 89 percent of Latinos; and saying “everyone can succeed in this society if they work hard enough” was deemed “not offensive” by 89 percent of Latinos and 77 percent of African Americans."PC Language

Finally, in The Atlantic, Yascha Mounk writes about political correctness as mentioned in the Hidden Tribes Report.

"Among the general population, a full 80 percent believe that “political correctness is a problem in our country.” Even young people are uncomfortable with it, including 74 percent ages 24 to 29, and 79 percent under age 24. On this particular issue, the woke are in a clear minority across all ages."Mounk then goes on to describe the demographics of those espousing PC language.

"So what does this group look like? Compared with the rest of the (nationally representative) polling sample, progressive activists are much more likely to be rich, highly educated—and white. They are nearly twice as likely as the average to make more than $100,000 a year. They are nearly three times as likely to have a postgraduate degree. And while 12 percent of the overall sample in the study is African American, only 3 percent of progressive activists are. With the exception of the small tribe of devoted conservatives, progressive activists are the most racially homogeneous group in the country."Rich, educated, and white? That sounds a lot like the elitist group described in the Quillette column. Now, just because a group is racially homogeneous and ideologically orthodox does not mean they have a hidden elitist agenda. But it does weaken their "if you disagree with me you're a racist bigot" argument when most minorities are outside their bubble and, in fact, disagreeing with them. And it does suggest they do not necessarily represent the values of the people they are trying to help.

Friday, November 8, 2019

Why I'm not an activist

“there is no such thing as a not-racist idea,” only “racist ideas and antiracist ideas.”

-Ibram X. Kendi

"Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."This is a defense of moderation, or better yet, my concept of civility. Actvists tend to commit the third great untruth: believing that life is a battle between good people and evil people. And since those not fighting against us are not fighting with us, they have chosen evil.

-President George W. Bush

Moderates are hard to define because we are not a monolith. But here are some reasons we do not engage with your wars.

The wrong action is often worse than no action. In the President Bush quote above, invading Iraq ended up being a terrible idea. Many moderates are slow to action, requiring careful consideration, because taking the wrong action is worse than no action. We would have been better off never invading Iraq, obviously. Inaction probably delayed the civil rights movement, but I believe that is the exception rather than the rule.

I don't trust all of the people on your side. Fighting racism sounds great. I would love to punch a Nazi in the face. But I have some reservations. First, the Kendi quote above comes from a review of his book in which he proposes an anti racist amendment to the Constitution that would:

"establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees... The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas."That sound pretty far from punching Nazis and terrifyingly totalitarian. Oh, and about punching Nazis. I don't trust your side to determine who is a Nazi. Especially after Antifa beat a Bernie Sanders supporter just for carrying an American flag.

I don't prioritize my desires the same as you do. This isn't about privilege; it's about what I think is most important. I don't think we can have a functioning society without trust, which is why I prioritize depolarization above Medicare for All or building a wall.

I would love to have a health care system that provides for everyone and costs less. I'm skeptical it can be done, but I'm more worried about what happens when you try to force half the country off the private insurance plan they prefer. Our system does not work without cooperation and I'd rather repair the system than blow it up.

I don't think all your facts are accurate. I hate racist police officers. The one who shot Philando Castille should absolutely be in prison. I'll sign that petition for you. But I won't march with a group that also marches for Michael Brown, whom I believe was shot because he attacked a police officer.

I'm also picky about systemic racism. Data has convinced me there is no racial bias in arrests for violent crimes. Sentencing? Yeah, there probably is a racial bias. But in my experience, the activists don't offer an à la carte menu to support. It's very all or nothing. Don't confuse my nuanced thinking with inaction.

I hate coercion. I don't love the status quo, but I would rather live in a world with current levels of inequality and injustice than one in which we give one person or party absolute power to change things as they see fit. There's just no way that power won't be abused once it falls into the wrong hands. Which it will. The incentives are too great.

Friday, October 25, 2019

Race, Grammar, Bullying, and Belonging

Some years ago I began the David Foster Wallace essay "Authority and American Usage." As a writer, I'm interested in grammar, particularly the battle between prescriptive and descriptive advocates, and Wallace seemed a good authority on the issue.

I read the essay before bed and never finished it. I picked it up again a few weeks ago and finally finished. I'm glad I did because it took many turns I did not see coming.

Wallace begins with a mention of how he was a grammar Nazi (he prefers SNOOT, or Syntax Nudniks of Our Time ) as a child and how it held him back with his peers.

This is a lesson many white children do not have to learn. Their dialects seem to more closely transition into SWE and there isn't an aversion to distancing themselves from an outgroup, since SWE is mostly spoken by white people.

I read the essay before bed and never finished it. I picked it up again a few weeks ago and finally finished. I'm glad I did because it took many turns I did not see coming.

Wallace begins with a mention of how he was a grammar Nazi (he prefers SNOOT, or Syntax Nudniks of Our Time ) as a child and how it held him back with his peers.

"... this reviewer regrets the bio-sketch's failure to mention the rather significant social costs of being an adolescent whose overriding passion is English usage..."He then moves into how there are are myriad dialects other than Standard Written English, and we all (Black, White, Asian, Latinx, etc.) speak more than one of them.

"Fact: there are all sorts of cultural/geographical dialects of American Usage — Black English, Latino English, Rural Southern, Urban Southern, Standard-Upper Midwest, Maine Yankee, East-Texas Bayou, Boston Blue-collar, on and on... many of these non SWE (standard written english) type dialects have their own highly developed and internally consistent grammars, and that some of these dialects' usage norms actually make more linguistic/aesthetic sense than do their Standard counterparts... nearly incomprehensible to anyone who isn't inside their very tight and specific Discourse Community (which of course is part of their function)."Wallace then goes into the tribal nature of learning a local dialect: it has an ingroup/outgroup function.

"When I'm talking to RMers (Rural Midwestern) I tend to use constructions like "Where's it at?" for "Where is it?"and sometimes "He don't" for "He doesn't." Part of this is a naked desire to fit in and not get rejected ... but another part is that ... these RMisms are in certain ways superior to their standard equivalents."

"Whether we're conscious of it or not, most of us are fluent in more than one major English dialect and in several subdialects and are at least passable in countless others.... the dialect you use depends mostly on what sort of Group your listener is part of and on whether you wish to present yourself as a fellow member of that Group."

"A dialect of English is learned and used either because it's your native vernacular or because it's the dialect of a Group by which you wish (with some degree of plausibility) to be accepted. And although it is a major and vitally important one, SWE is only one dialect... There are situations ... in which faultlessly correct SWE is not the appropriate dialect."Now it gets really interesting. Wallace does something that Chris Rock talks about in his latest Netflix special that kinda sounds like justifying bullying. But it also supports the importance of free play and socialization for children. They need to learn from one another as much as they learn from adults.

"Childhood is full of such situations. This is one reason SNOOTlets tend to have such a hard time of it in school... The elementary-school SNOOTlet ... is duly despised by his peers and praised by his teachers. These teachers usually don't see the incredible amounts of punishment the SNOOTlet is receiving from his classmates, or if they do see it they blame the classmates and shake their heads at the sadly and viscous and arbitrarily cruelty of which children are capable.

"Little kids in school are learning about Group-inclusion and -exclusion and about the respective rewards and penalties of same and about the use of dialect and syntax and slang as signals of affinity and inclusion. Kids learn this stuff not in Language Arts or Social Studies but on the playground and on the bus and at lunch... what the SNOOTlet is being punished for is precisely his failure to learn... the SNOOTlet is actually deficient in Language Arts. He has only one dialect. He cannot alter his vocabulary, usage, or grammar ... and these abilities are really required for "peer rapport" which is just a fancy academic term for being accepted by the second-most-important Group in a little kid's life."

"One is punished in class, the other on the playground, but both are deficient in the same linguistic skill—the ability to move between various dialects and levels of "correctness," the ability to communicate one way with peers and another way with teachers and another with family and another with T-ball coaches and so on. "Finally, Wallace comments on race. This sounds like roundabout way of talking about "talking white," a contentious subject that many people think is made up. Others, like John McWhorter, think are all too real. It's also a good explanation of why learning Standard Black English, and dismissing SWE, is so important to many African Americans, it helps ensure ingroup distinction.

This is a lesson many white children do not have to learn. Their dialects seem to more closely transition into SWE and there isn't an aversion to distancing themselves from an outgroup, since SWE is mostly spoken by white people.

"Here is a condensed version of a spiel with certain black students who were bright and inquisitive as hell and deficient in what US higher education considers written English facility:Overall it was a really interesting read about how people use language to both fit in and to exclude.

'...when you're in a college English class you're basically studying a foreign dialect... the SBE (Standard Black English) you're fluent in is different from SWE in all kinds of important ways...

It's not that you're a bad writer, it's that you haven't learned the special rules of the dialect they want you to write in."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/47775331/partisanship2__1_.0.0.jpg)