She makes some good points and some bad ones, which I will respond to.

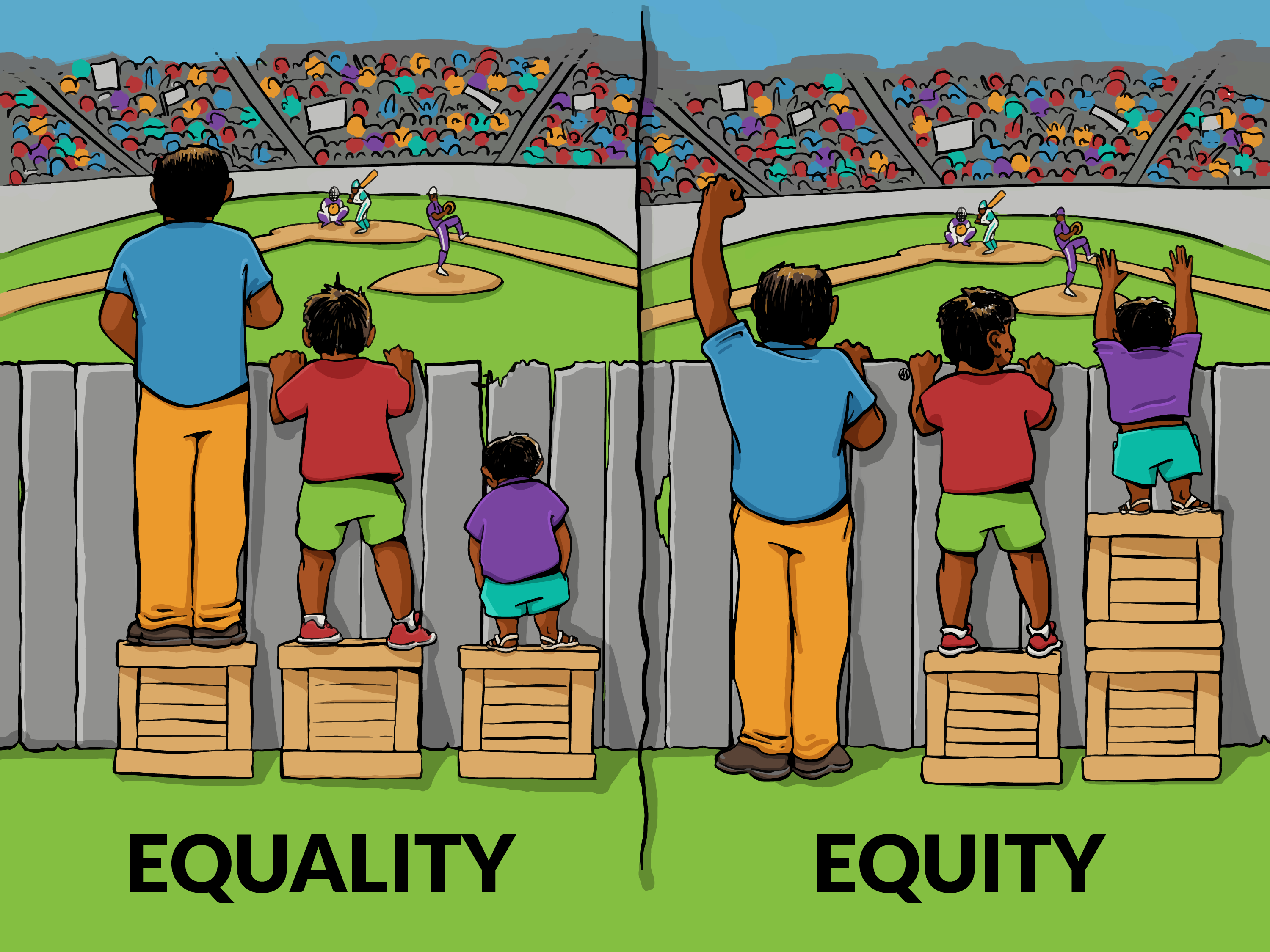

"Zuckerberg’s statement startled me, partly because he was more adept at defending Thiel than he was at addressing Facebook’s failure to hire black employees. (Facebook is about 2 percent black. Its board is 100 percent white.)"People love to point out the racial diversity of an institution they don't like. I don't know if Knibbs is suggesting a lack of equality or a lack of equity. Is she suggesting Zuckerberg is racist because he's not hiring enough blacks or is he racist because he's not manipulating his hiring process and discriminating against other races in favor of blacks?

How many qualified African-Americans are there to work at one of the most successful companies? According to this, 13.7% of Harvard's student body is African-American. Assuming the alumni demographics are similar, there should be quite a few African-American elites out there for Zuck to choose from. So Knibbs might have a point.

Nutpicking

"The push for “ideological diversity” (SCARE QUOTES!) as a curative confuses the benefit of dialectical learning with the notion that all ideas are worth debating. History is littered with horrible ideas that aren’t worth poking holes into during a question-and-answer session. “The earth is flat,” for instance. “Castrating homosexuals is an acceptable punishment for homosexuality.” “Slavery is good.” “Women’s suffrage is incompatible with democracy.”'

"In contemporary arguments for “ideological diversity,” the ask is more moderate: It’s not that campuses need to purge Marxists as much as they need to let a few more Ayn Rand aficionados and ethno-nationalists onto the tenure track."One of the things Knibbs does is take the worst representation of her outgroup and use it as an example of what "ideological diversity" might look like. (She also conflates "diverse" ideas with those lacking merit.) She might counter by saying that this is what will happen if we open the floodgates to different thinking, these bad ideas will get through.

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, the author becomes transfixed with trying to define "quality." He says it's something that's both objective and subjective at the same time.

For example, I hate country music. But even I can distinguish between high quality country music like you'd hear on the radio and low quality country music performed by some hack who can't stay in key. My point is, I don't think it's as hard as people think to distinguish high and low quality ideas from our outgroup.

For example, Heterodox Academy doesn't call for all loons to come give college lectures. It calls for credentialed professors from different ideologies to be welcomed into the academy so that their biases will cancel each other out.

Even the fringiest of the left wouldn't expect Zuck to hire homeless people of color to write code for him if it meant more racial diversity. Merit still matters.

The Perception Gap study shows that more than 3/4 of Republicans agree that racism is still a problem (Democrats predicted the number to be about 1/2, hence the name "Perception Gap"). Our outgroup isn't dominated by the crazies; we just think they are.

The other thing that helps is to picture ideologies as the emotions that drive them rather than their worst representation. That's why I like Arnold Kling's Three Languages of Politics, it helps me see conservatives as people who fear the decline of civilization rather than people who want a military state to keep minorities down.

Bad faith

"But the “ideological diversity” debate, again, isn’t really about allowing every horrid viewpoint equal standing. It is about creating a schism in which extreme conservatives appear a trampled class."

"When Zuckerberg used the phrase “ideological diversity” on a college campus, he was crouching behind the notion that the real problem is groupthink, not that Facebook did a bad job of hiring people of color to operate his company."

"I don’t know if Zuckerberg boasted of Facebook’s “ideological diversity” in keeping Thiel on its board to offer a deliberate olive branch to the right wing, or if he has genuinely conflated the value of having people with different perspectives working together with an idea that all perspectives are equally valid and deserving of a platform,"I hate bad faith arguments. They reduce people to flat, cartoonish characters. In fact, this is a good example of why we need more ideological diversity. The more we stay in our bubbles, the more we assume the worst about our outgroup. The more we communicate with those who do not think like us, the more we see nuance.

In the second quote above, Knibbs does raise an interesting point though. Do I think Zuck touts ideological diversity just so he can use that as an excuse for keeping his board 100% white? No (remember, his own wife is Asian). But is it possible to have ideological and racial diversity? I don't know but I fear that one comes at the cost of the other.

But, in good faith, I'm going to assume that which ever type of diversity you favor is because you think it's best and not because you want to live in a totalitarian state or because you promote the superiority of a certain race.

Simple stories

"Hemmer notes that conservatives eventually adopted the pro-diversity language of the left as an undermining tactic,"

The phrase “ideological diversity” is a Trojan horse designed to help bring disparaged thought onto campuses, to the media, and into vogue. It is code for granting fringe right-wing thought more credence in communities that typically reject it, and nothing more."These quotes remind me of Tyler Cowen's TED Talk about simple stories. In short: beware of them. Especially if you see words like "pure and simple" or "and nothing more", usually the writer is arguing in bad faith.

A good counter I like to give is to ask the person if it's possible to distinguish good faith from bad faith. Such as, "If conservatives truly believed that the best form of education came from heterodox thinking, how would you be able to distinguish them from conservatives who are only using that language to give a platform to white supremacy and nazis?"

Most people don't have a way of distinguishing, which makes their assumptions rather hollow.

The Power to declare racism

"When students come out against ideas like this, they aren’t succumbing to dumb mob-think. They are taking a reasonable stand against legitimizing hurtful, wrongheaded nonsense."

"Pundits are getting distracted by the dubious tactical approaches of a small minority of protestors instead of focusing on why they’re so upset in the first place — because discredited, offensive, and abhorrent (often right-wing) fringe viewpoints are now getting treated like they’re merely “ideologically diverse” instead of poisonous."Now we get into the muddy area of what is considered "nonsense", "fringe" and "discredited." Who is given the power to decide that? I would also argue that "hurtful" and "offensive" ideas are not precursors for wrong. Sometimes they are, but sometimes they are the result of not being exposed to different viewpoints.

The path to truth doesn't always feel good.

I guess what upsets me most about columns like this are that they take a topic that obviously is foreign to them, like ideological diversity, and spend the column writing about how the people who push it are evil instead of, I dunno, doing actual reporting. How about figuring out what this idea is and what drives people to feel that way? How about talking to some people outside your inner circle instead of lifting an email from your old boss without asking him?

The worst part is that she writes about the students who attacked Allison Stranger and wonders why pundits didn't focus on why they're upset, without a hint of irony as to why she is not focusing on why someone of a different ideology might think the way they do. (Unless she truly believes it's as simple as blatant racism. If so, try harder, Katie.)

I would be happier if the conclusion were something like: "I can understand the merits of viewpoint diversity, but I still believe that racial and gender diversity is more important and if I have to choose one I am going with the latter."

I really don't want to do this, but ...

"Murray coauthored 1994’s The Bell Curve, a discredited tract that argues for the innate intellectual superiority of white people over black people."Defending Charles Murray is not a hill I'm willing to die on, I disagree with him on many things and he is certainly to the right of me politically. But I can at least steelman his haters.

I find it inaccurate to say his work has been "discredited." It's been criticized and he has responded to the criticism.

Two chapters of the book talk about race. The rest of the book argues that intelligence is the best predictor of things like earnings, job performance, unwed pregnancy, and crime.

The fact that his thesis is controversial does not make it discredited. You could say lacking in consensus.

As far as I know, the research is solid. The question becomes how much can be extrapolated from the work? "Is IQ the best predictor of success?" is a good question to ask. And, even if true, should we withhold this information if it emboldens white supremacists? (Personally, my favorite take on IQ comes from Eric Weinstein.)

The value I do find in his work is that it pushes back against blank slatism; an idea that I feel has been discredited. However, blank slatism has enough support from credentialed academics that I find value in seeing it debated. Bad ideas don't go away by being pushed underground (that makes them more extreme), they go away by being proven wrong.

If it were up to me, I would determine which ideas are worthy of attention by merit and popularity. If there is a really good idea that no one is talking about, we should shed light on it. If there is a really bad idea that has become ascendant, we should show why it is wrong.

I also take umbrage with the last part of Knibbs' quote. If anything, Murray's work shows the "innate intellectual superiority" of Asians over everyone else.

Taking the low road

So let's engage in some bad faith reasoning. It sounds like fun.

There is a scene in Louie (yes, I'm going there) in which Louis C.K. and Parker Posey are on a date. She convinces him to come to the top of a roof and proceeds to stand on the roof's edge and look down. Louie, out of breath and starting to worry that she might be a little crazy, refuses.

What are you afraid of? she asks. She then infers that a part of Louie is afraid that he wants to jump, and that is why he doesn't want to stand on the edge of the building and look down. Posey declares, "I want to live. That's why I'm not afraid to look down."

Part of me wonders that the reason those in ideological bubbles refuse to listen to other ideas isn't because it legitimizes discredited ideas or will be hurtful to minorities. It's because a small part of them is scared it will change their mind.

Here is my plea: You might think a person is bad because the SLPC declared them a racist. But if you engage with them, you're probably not going be convinced that they are right and run off to join their tribe. However, you might come to believe that they are not actually racist.

So don't be scared. Come to the edge. If you are confident in your beliefs and identity, I guarantee you won't jump off. But you might see the world from a new angle and gain a new appreciation.