My favorite podcast is called

The Rewatchables, which is just three dudes rehashing what they love about an old movie. It has taught me how different subsequent viewings are from the first one. You pay more attention to subtlety rather than trying to follow the plot, because you already know what happens.

The first novel I read in years is called

Station Eleven, which is the basis for an HBO series I’ve already watched several times. So I already had a sense of where the plot and character development was going and I could focus on the subtlety.

I just haven’t had the appetite for something new in a while and I don’t think I’m alone.

On his Plain English podcast, Derek Thompson says:

“This year, the song of the summer is arguably Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill”—which was released in 1985. It was launched by the most-watched global TV show of the summer, Stranger Things—an homage to the 1980s. In movies, the biggest hit of the season is Top Gun: Maverick—a sequel to the 1986 film. The ’80s was four decades ago!

The triumph of nostalgia and familiarity in culture is deeper than one summer. The five biggest movies of this year are the second Top Gun, the second Doctor Strange, the sixth Jurassic Park, the 14th Batman-related film, and the fifth Despicable Me.

The data now shows that more than 70 percent of the songs streamed are old songs."

Similarly, in The New York Times

Wesley Morris writes,

“In “Maverick,” the comedy is that no one’s as qualified as Cruise. For a couple of weeks in August, our No. 1 movie was “Bullet Train,” an intermittently funny, mostly tedious crime-thriller that requires Brad Pitt to fight younger prospects — Brian Tyree Henry and Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Zazie Beetz and Bad Bunny — and casually kill most of them. They want what he’s got: a briefcase full of money, but his stature, too.”

Fearing what's next

The plot of

Tenet revolves around some group of people in the future who are trying to reverse the flow of time, to make it run in reverse. Why? Something to do with climate change, I think. But the point is the future was bad and they viewed the past as better so they went to extraordinary lengths to reverse the flow of time to get away from the future.

I can’t help but feel that something similar is happening culturally. We seem to be afraid of the future and more nostalgic than ever. It’s even hurting creativity.

Songs don’t even have key changes anymore.

People have been predicting that DALLE 2 will disrupt graphic designers. But all the AI does is take inputs and say “this looks like something a human would create.” As far as I can tell, AI doesn’t have the ability to innovate and create new artistic styles, its creations are based on existing styles. Maybe this is what AI really disrupts, creativity.

CancelledPeople like to say that you can’t say the type of things that George Carlin said anymore, it would be too controversial. But that’s not entirely true, because Dave Chapelle says controversial things and people have been trying to cancel him for years. But what I think is true is that no up-and-coming comic could do Chappelle’s exact act and survive. Chappelle, like Cruise and Pitt, has built up enough of a reputation and a loyal audience to make it worth it for Netflix to keep platforming him, despite the number of people calling for his head.

He has what Erik Hoel calls “immunity to gossip.”

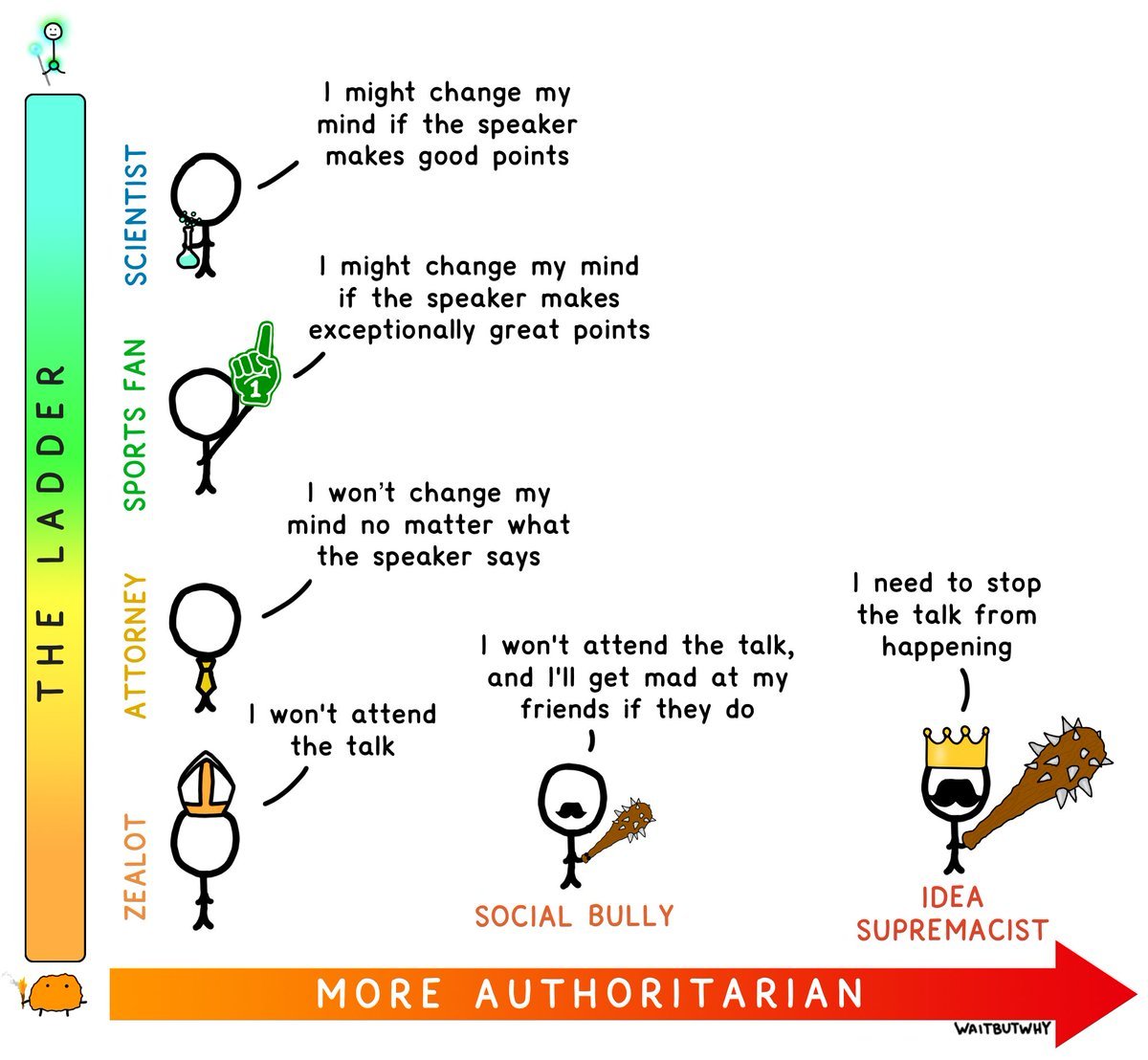

In a popular Substack post, Hoel coined the term “gossip trap” to describe the default setting of most social groups that prevents the formation of civilization, and how we seem to be falling back into it.

“Being in the Gossip Trap means reputational management imposes such a steep slope you can’t climb out of it, and essentially prevents the development of anything interesting, like art or culture or new ideas or new developments or anything at all. Everyone just lives like crabs in a bucket, pulling each other down. All cognitive resources go to reputation management in the group, leaving nothing left in the tank for invention or creativity or art or engineering.”

For him, civilization was a solution out of the gossip trap.

“For what are the hallmarks of civilization? I’d venture to say: immunity to gossip. Are not our paragons of civilization figures like Supreme Court justices or tenured professors, or protected classes with impunity to speak and present new ideas, like journalists or scientists?”

I applaud Hoel for using a simple term like “gossip trap” to describe the phenomena, rather than something nerdy and opaque like “socialized stigma inertia”. But I still think there’s a better way to describe what he’s talking about.

Surviving popularity

Gossip is done behind people’s back. That’s not what we’re describing here. What we’re describing is this: someone who holds subjectively dangerous/harmful views is getting too much prestige (trying to climb out of the bucket) and we respond by pulling them back down.

This blog post best capsulated what I'm talking about (you have to scroll down until you get to the Caviar Cope section). I saw T

he White Lotus and thought it was okay. But many people in my social circle loved it. They all shared similar traits: left learning, highly educated, white, middle to upper class folks who tend to hate the wealthy.

The writer notes that viewers of Succession, The Menu, and The White Lotus have this internal monologue like this:

"I would love to own a yacht, but I'm too smart and mentally healthy to be that rich. So I'll just watch these pathetic losers on their yachts, to enjoy the experience, while also basking in my superior intelligence and well-being."

The White Lotus leans right into the gossip trap. It tells the viewer, "You know how all wealthy people are evil? Come watch this show where they all get humiliated and you get to laugh at them." The show is an avatar for pulling people back into the bucket.

The Cancel Paradox

Hoel’s idea of the gossip trap is his attempt to answer the sapiens paradox: why did it take so long for humans to invent civilization. But he actually does a better job of answering the origins of our current cancel/accountability culture (a common criticism of the idea of cancel culture is that "it's just people finally being held accountable." Fine, you agree such a shift in norms has occurred. You're just quibbling about it's label. In my effort to be inclusive, I've used the phrase "cancel/accountability culture.").

My understanding of Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature is that asking something like “why is there so much violent crime in east St. Louis?” is asking the wrong question when violence has been the norm for most of human history. Instead we should look at a quiet, low-crime community and ask why there isn’t violence.

So w/r/t the origins of cancel/accountability culture, maybe we’re asking the wrong question. Should be asking: how did we go so long without cancel/accountability culture? Hoel’s answer would be civilization, which involved building superstructures that create immunity from gossip/canceling. The cause of our current regression has been the age of information and transparency, which makes it easier to pull people back into the bucket with us and it’s made it harder for anyone growing up in this era to take creative risks when reputation management is so important.

From Lohan to Probst

But I’ve already said that gossip and high school culture isn’t the best metaphor for what’s going on. So what is? The TV show Survivor.

There are two ways to advance in Survivor. The easy way is to win competitions and gain immunity from being voted off the island. The other way is to not get voted off the island, which you do by getting people to like you, but not seeing you as a threat.

This is where we are in our current culture. There is no more immunity so everyone is trying to be liked but not seen as a threat. (I should admit that I've never actually watched a full episode of Survivor.)

One of the most popular current comedians is Nate Bargatze. His secret?

He never says anything offensive. Seriously,

jump to the four minute mark in this bit he does about global warming. "Global warming, we gotta stop it. Or ... more of it? I don't really know which way we gotta go." He's gaining popularity because no one sees him as a threat. But if he ever works a political stance into a bit, watch the crabs come for him.

Civilization shrugged

This might explain our current cancel/accountability culture, but I’m still having trouble wrapping my head around Hoel’s point. He asserts that gossip is a “leveling mechanism” that has historically prevented, eg talented hunters from accruing too much power. These hunters are mocked and belittled by their peers and dragged back down into the bucket.

He then writes that civilization is a superstructure that levels leveling mechanisms. This seems to suggest that what allowed us to crawl out of the gossip trap and invent civilization was allowing individuals to accrue too much power. That’s some John Galt/Ayn Randianism shit right there.

If hunter/gatherer life is about tribes sharing the resources available (ie food), then agriculture/civilization is about increasing the amount of resources available and not sharing the new supply.

If this is true, then the libertarian mantra “the most common human trait isn’t greed, it’s envy” might be right. Capitalism isn’t about greedy powerful men exploiting poor workers and squirreling away resources for themselves. It’s about, well, greedy powerful men creating new resources and not sharing them as the rest of us look on with envy.

A Way Out?

So what would a superstructure that allows for creative risks and protects reputation look like? It might be

Ontario's Human Rights Code. If you've been following any of the culture wars lately you may have read about a transgender teacher teaching a class while wearing large prosthetic breasts with protruding nipples. The school board has defended her right to do so, as she is protected by the law.

As far as freedom of expression goes, this example is a weird hill to die on. But in our current cancel/accountability culture, the fact that this unpopular personal decision is allowed to take place is proof that we can still create structures to climb out of the gossip trap.

Steelman Time

This seems to apply for comedy and movies, but not TV. We are in the golden age of television where creativity doesn’t seem to be a problem. So I think the gossip trap only applies to individuals who gain too much prestige. And the fact that I’m resistant to starting a new book or TV series might have more to do with the paradox of choice than some “end of culture” phenomenon.

But we'll wait and see. Maybe writers and producers have been around long enough to build up a reputation that immunizes them against cancellation. We'll have to see if the creativity stagnates with the next generation of writers and directors.

But for now this is the best explanation I can come up with for the current culture war.